The Great Divide

Although the need to rebuild Japan must have been clear to everyone, knowing where and how to begin was surely difficult for most. Certain was that the Japanese and American government perspectives toward the US presence in Japan were very different. Whereas the Japanese viewed the American occupation as a temporary forward position進駐 of US troops on Japanese soil, the US government viewed its presence as a more permanent occupational force 占領 in control of Japan's destiny. In contrast, the Japanese public was likely torn between US propaganda and the continued control of Japanese society by the Japanese government. The presence of US troops and a variety of obvious political and social reforms must have suggested to many that the US government was in control. The obvious absence of change in other key areas, such as personal security, made it clear that the Japanese government was still in power. Surely, the Japanese public took advantage of whatever avenues of opportunity were offered them -- no matter the source. Unlimited selection is not a common feature of hard times.

In the absence of sufficient understanding of the Japanese language the US government could only control what it observed. As the Japanese provided the bilingual ability necessary for the understanding and interpretation of these observations, the US government's ability to bring about change was largely dependent on the willingness of the Japanese people and government to cooperate. In other words, the Japanese government could show the US government what it wanted to see and conceal -- or at least make it difficult to reveal -- what it did not. In other words, the unconditional surrender無条件降伏 was rendered conditional条件降伏 by the inability of the US government to understand clearly what was actually transpiring.

unresolved misgivings

Having spent the prior half-century in the belief that one's national mandate was the protection of the Asian Pacific from Western colonial powers many Japanese must have found it difficult to believe that the West had once again forced its way into Tōkyō Bay東京湾 -- this time, however, with a military capability vastly more powerful and many times more numerous than a century before.

There was plenty of evidence that something had gone wrong, but who was to blame? Had the intentions of the Japanese emperor not always been well meant? Had those intentions not always been in the best interest of the Japanese people and its closest neighbors? Afterall, the rubble that lay before Japan's feet was not Japan's doing; the people who dropped the bombs and pulled the triggers on Japanese citizens were not Japanese. Moreover, the soldiers who now occupied Japanese soil were the very same whom Japanese soldiers had struggled so hard to defeat. Was it not their very presence that the Japanese people had sought to avoid?

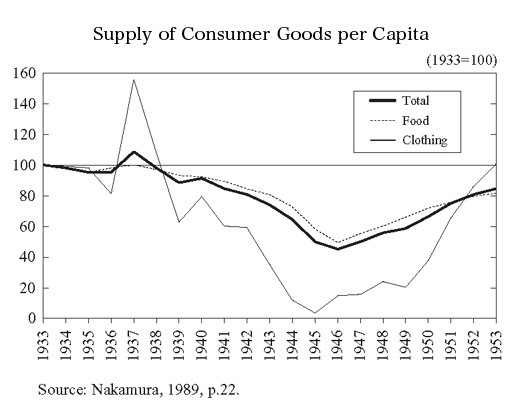

In contrast, it was not the American government that had brought about the impoverishment of the Japanese people. Food, clothing, and medicine were already in great shortage before the Americans arrived, and the shortage had started long before the bombing began. Furthermore, it was the American -- not the Japanese government who was now supplying the Japanese people with the food and medical care that they so badly needed.

Many Japanese were probably wondering whether Western domination had been inevitable? Japan had been the last in a long series of colonial conquests to have fallen victim a century before. And, Great Britain's help to stay the hands of the Germans and Russians only decades earlier was hardly a gesture of kindness. Even the United States had once been a former British colony. Alas, Japan's attack on the United States was not so very different from the United States' declaration of war and struggle for independence against Great Britain. The United States had been a clear threat to Japan's Western Pacific empire, and in the end, one could only wonder whether national governments would ever stop competing for world domination.So, where was the shame in losing to one's military superior? Either the war had been a mistake and heads would role, or one could be proud that one had done his best to delay the inevitable.

Rebuilding trust between two great nations that had just waged war was going to be difficult in the absence of a shared language and culture. Moreover, unconditional surrender left little room for negotiation. Certainly, there was no confusion between voluntary cooperation and a strategic defensive response in the face of adversity. This was not the first time that Japan was compelled to handle a foreign presence on its own soil.

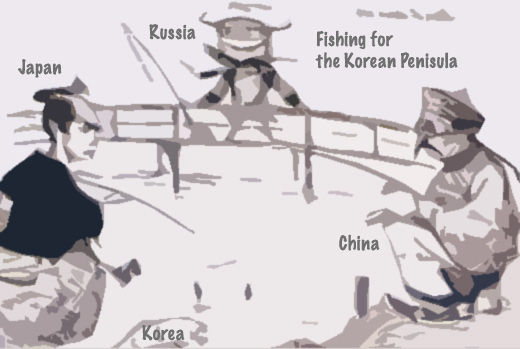

There was another important problem that would eventually prove difficult to resolve -- Japan's historical legacy. The United States did not become an important stumbling block in Japan's overseas expansion until very late in the game. There were other players much closer to Japan's shoreline with whom Japan had shared a conflictual relationship -- the Chinese, the Russians, and the Koreans. Though the Japanese and Koreans had a long, sometimes intimate, sometimes troubled history dating back many centuries, the relationship between Japan and China was very different. Like the Koreans, Japan owed much of its culture, language, and society to the Chinese. China had never forced its way onto Japanese soil, and Japan would never have become the great nation that it was, had it not been for the Chinese. In short, Japan's effort to colonize China was viewed by most as a pompous, ungrateful act of aggression. In contrast, the Japanese and Russians shared little in common that could not be summarized as territorial conflict. In this sense, they were natural enemies of late 19th and early 20th century colonial expansionism.

Finally, it is one thing to be unable to agree on one's precise sphere of influence; it is quite another to impose one's way of life on one's adversary. Indeed, what makes it so difficult for many Japanese to get along with their closest neighbors is the air of lingering superiority among the Japanese, and the perceived need of Japan's closest neighbors to prove that these feelings are undeserved.

This said, Japan was not defeated by its former colonies, and the imposition of American society on both the Japanese and the Koreans has left a lasting impact -- both positive and negative.

historical backdrop

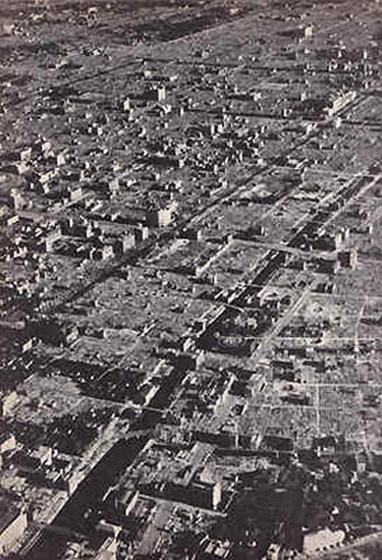

The US marched into Japan, like their enemy, weary of war. The many sleepless nights in mosquito-infested, tropical jungles or on the high seas with sudden, dramatic swings in climate must have worn heavy on the spirit of US troops. Nearly everyone endured these conditions bereft of family, forever wary of an unknown, dangerous, and vicious enemy. The incessant pounding of exploded munitions, the endless hum of destructive machinery, and the agonizing cries of fellow humans must have resulted in deep, traumatic scars for many. Surely, every soldier, sailor, marine, and aviator had endured these conditions to a different extent. Certainly most were very happy that the war was over and they were on the winning side. Despite their suffereing, these weary troops did not find themselves at home enjoying the life-style that they one believed threatened, but rather on their defeated enemy's territory -- still another foreign land among a people whose language they did not speak and whose culture they did not know, a land whose urban centers they had devastated with napalm and nuclear radiation.

What a miserable lot they must have thought, when US soldiers viewed the Japanese nation close up for the first time. Many urban residents had been made homeless and driven to the countryside in search of new shelter. Many more were without food and clothing. Even the means to produce the barest necessities had been mercilessly destroyed by the carpet bombing of Japan's most important urban centers.The war was over, but the victory could hardly be felt. What lay before the feet of both the victor and the vanquished was the same -- misery, destruction, and entrapment.

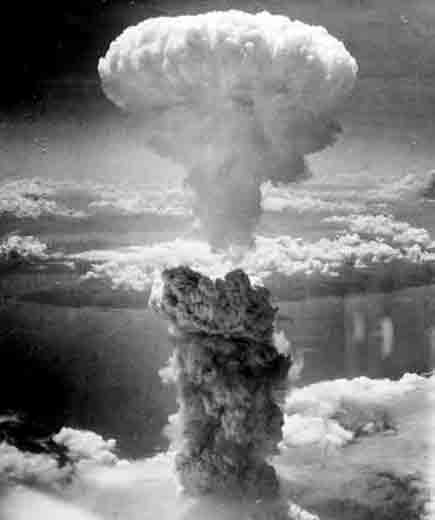

It is difficult to know how many Americans witnessed the awesome destruction that laid to waste the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki earlier that summer. Surely those who saw it stood in awe and felt gratitude that it was their government -- not Japan's -- that had learned to build the bomb first. Indeed, American feelings toward the Japanese must have been a mixture of hatred, pity, and curiosity.

The US did not arrive in Japan as a good friend seeking reconciliation after a bitter squabble, nor as a close neighbor with a long history of struggle ending in alternating victory and defeat; rather it arrived as a dominating alien race and embittered enemy who shared little in common with Japan that could not be summarized as a mutual conflict of interest. The point of contention was, of course, Japan's increasing dominance in its own backyard.

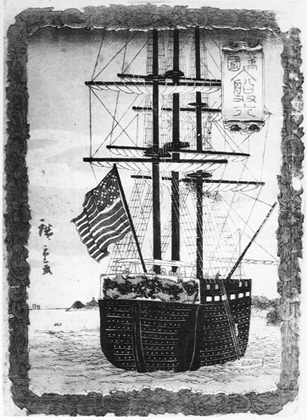

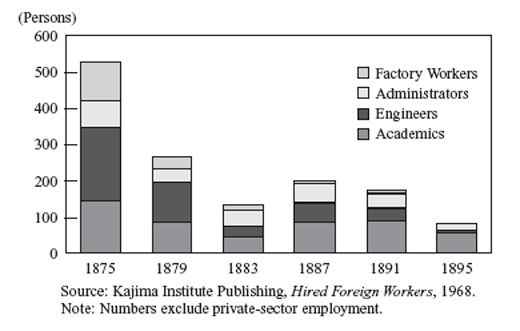

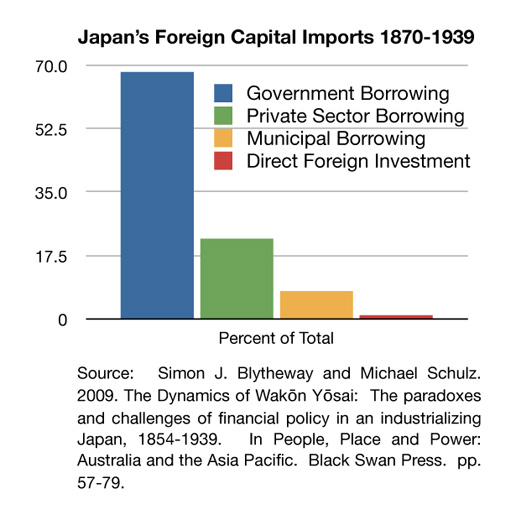

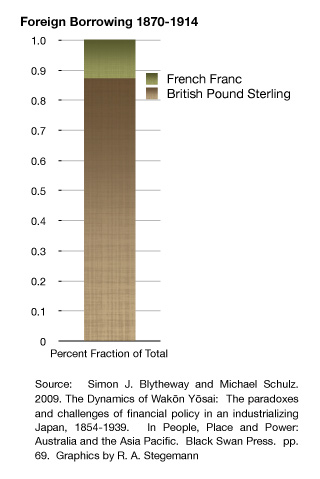

Surely, during the 90-odd years since Commodore Perry's first arrival in Uraga浦賀 Japan's relationship with the United States had improved; but the US was only one of several major powers with whom Japan maintained diplomatic ties, and it had hardly been the most important. Firstly, Japan's knowledge of Western technology was drawn from a variety of countries; Portugal, the Netherlands, Great Britain, France, Germany, Belgium, the United States had all received diplomatic missions from Japan. Nearly all of these countries were also an important source of scientific expertsお雇い外国人 whom Japan had hired to advise and train Japanese businessmen, government officials, and students. Secondly, most of Japan's rapid growth during the Meiji明治時代 and Taishō大正時代 periods was financed by British and French capital. Only after the close of World War I, when European capital markets were tight, did Japan turn to the United States. By the 1930s, however, even financial capital from the United States was difficult to obtain. Furthermore, the Japanese financial system was modeled after the French, not the US system, and Japan's central bank was nearly identical with the Belgian National Bank (BNB). Thirdly, though foreign direct investment from the United States increased after World War I, it remained relatively small as a proportion of Japan's capital imports. Indeed, until Japanese manufacturing came of age at the turn of the century, Great Britain was the sole supplier of steel, ships, and locomotives to Japan. Even Japan's early steel industry was modeled after German technology -- not American. Fourthly, though trade between the United States and Japan was initially very important, it remained small throughout most of Japan's development. As Japan grew, it focused increasingly on its closest neighbors from whom it could obtain badly needed raw materials on the one hand, and more easily sell its final output on the other.

By the time World War I broke out Japan was already well along the path toward becoming the region's dominant power. As a close British ally before the war Japan helped Great Britain to keep the Russians and French in check, and during the war Japan assisted Great Britain in driving the Germans out of the region. This alliance was criticized by the United States, Australia, and New Zealand who viewed Japan as an intruder to their own colonial interests. As a result, the alliance was restructured after the war in a broader treaty that helped the United States secure a stronger foothold in the Western Pacific.

In the end, what Japan had been doing in the region was little different from what every great power at the turn of the century was doing the world over. Simply, Japan enjoyed closer racial, cultural, historical, and linguistic affinity with those whom it sought to exploit and believed itself better able to offer the regional security and stability大東亜共栄圏 desired by Western powers -- this, despite its many years of insularity鎖国. Fearful of further intrusion from the West Japan had issued with enormous energy and force from the same doors that it had once struggled to keep shut. As a result, the focus of power suddenly shifted, and the Western powers who had once dominated the region felt threatened. Indeed, before Japan's rise to power alliances among the great powers in the region had shifted steadily with the winds of opportunism, as everyone sought to catch prize fish in the great colonial fishpond.

Unfortunately, Japan's biggest asset was also its biggest handicap. If there were common ground between Japan and the United States that was not rooted in the geopolitics of the region, then it was slight; neither nation could claim membership in the European club. On the one hand, its geographical proximity to the region made it a knowledgeable negotiating partner with the region's lesser powers; on the other hand, Japan was not a partner in the European club and only welcome in the game as a junior partner aspiring for full membership -- membership that could, but would never be granted. Japan was not a nation with a large Christian population; nor were there many Europeans or North Americans who could claim Japan as their rightful home. Moreover, Japan's outreach to Europe and the United States was politically motivated by its desire to defend its own way of life. Obviously there were certain things that Europe and the United States could do better; for Japan it would be enough to acquire the technology and know-how that would permit it to perform as well, if not better追付け、追い越せ. Japan's goal was then, as it is today, self-determination. The acquisition of European and North American culture was an important means to achieve this goal.

The differences between the East東洋 and West西洋 were, and remain today, both large and numerous. Let us not be fooled by the recent appearance of globalism. Though the technology that we use is obviously similar, and those who produce and distribute it are often the same, important differences can be found in those who control and utilise it, and sometimes, if not often, in how it is used. In order to understand these differences it is not enough to take anchor in another's port, set foot on another's tarmac, or reside in a luxury resort where everything looks and behaves similarly. One must escape these often sterile international sanctuaries of comfort and convenience and reside among the native population.

the abyss

What many East Asians see as meaningful, carefully designed, micro-pictures日本書体 of ancient thought and knowledge, the average US soldier must have viewed as meaningless hen scratches drawn by overworked East Asian hands. What most Japanese regard as convenient, dignified, multi-purpose, easy-to-use eating utensilsお箸, the same soldier must surely have viewed as pairs of unwieldy, crude, wooden splinters - too big for picking one's teeth.

These same troops surely observed as Japanese defecated in the open, barren fields that once hosted their now devasted homes. Then too, bathing nude with others of the same or opposite sex in a remote hot spring温泉 or neighborhood bathhouse銭湯 must have attracted some and repulsed others depending on their upbringing. In the end, much of what these servicemen observed was probably little different than what they had already experienced in other settings across the Western Pacific. After all, they were not tourists on vacation in a tropical paradise, and devasted infrastructure and cultural differences were abundant everywhere. More important, perhaps, was the contrast between the heavy, suffocating, leather boots that they wore and the light, open, footwear or barefeet of their reluctant hosts. Accordingly, the barbed wire that often held these two sides apart surely distorted the reality of the observed and their observers.

On those rare, but sometimes frequent occasions, where Japanese and Americans came together under normal conditions, one cannot imagine either side being very eager. After all, fraternizing with the enemy, except to gain intelligence, must have been generally discouraged. In contrast, imitation of the enemies habits for the purpose of comical disdain was likely, but separately, well applauded by everyone. In war, one cannot afford to view the enemy as the fellow human being that he truly is, for killing and maiming him would otherwise be difficult. Occupation is not so very different, as one's presence is unwanted and one's intentions are mistrusted. The absence of knowledge of the culture of the other side can make even the simplest attempts at communication difficult.

No matter. Communication does not occur in a cultural and linguistic void, and in the absence of a good understanding of the conceptual and behavioral habits of the other even the simplest attempts at communication can prove difficult.

A Japanese bows会釈 towards everyone with whom he wishes to communicate and often towards those whom he wishes he had never met. Americans, on the other hand, mock such behavior as a sign of subservience. The Japanese people are a uniformly mannered and polite people, and it takes substantial time to understand the subtle nuances that differentiate a Japanese snub from routine Japanese politeness. How many of the approximately three hundred thousand US serviceman present in Japan after the war, and the many tens of thousands that remained long after the occupation, ever came close enough to the Japanese people for a long enough period to understand these differences and interpret them?

The Japanese are a gregarious people who spend much of their time in groups. Unlike Americans who fill an entire rooms with the most trivial of information, Japanese tend to speak in quiet whispers that can only be heard with the best of attention. What would a US serviceman typically have thought when he saw a group of Japanese huddled together and laughing? Maybe that they were plotting to steal his lunch? In normal Japanese society one rarely enters into a heated discussion with anyone that does not end on the politest of notes. How many Americans can say the same for their own society?

Of course, these troops were not visiting anthropologists on a field trip. Neither, were they tourists pampered with fine meals and fresh linen every morning as they planned their day's itinerary of popular Japanese tourist attractions. Although they were surely an expeditionary force, neither were they in search of novel rock formations, exotic wildlife, and splendid landscapes. This is not to say that they did not experience these things; rather that they were often experienced along with insect, snake, and spider bites -- to say nothing of the stench of latrines dug with shovels, helmets, and bare hands. Worst of all were probably the orders that they received from distant high commands telling them to prepare for, and endure still another combat assault.

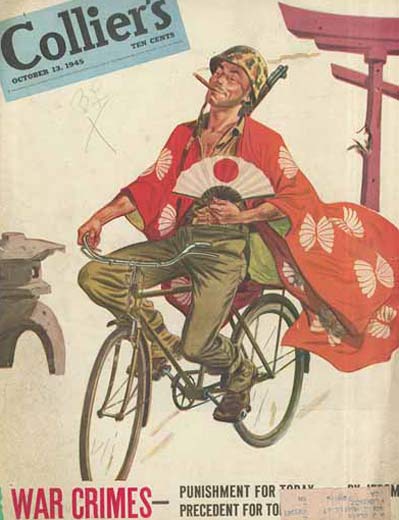

When the war broke out and the draft was put into place, those who requested an assignment to the European front where they could visit their father's, grandfather's, and great grandfather's birthplace, often found themselves building bridges and runways in Papua New Guinea. For many of these and others, the first time they had heard of Japan was in Jr. High School when they saw a caricature of a Japanese devil raping a defenseless girl in a distant land called China. Maybe they had even seen Chinese pottery in a local museum, or a Japanese fan扇子 in their dentist's office and wondered about its origin. Is it likely that they had even heard of Pearl Harbor before it was bombed? Though a distant memory for some this bombing surely remained a vivid memory for others; hatred is an important emotion often nurtured for the purpose of focusing on the enemies destruction. For still others, there was no need to replay a distant event that was never experienced directly. These latter had only to remember the day their best friend was dismembered by a piece of flying shrapnel or the conditions under which they were denied the opportunity to watch their own son or daughter mature. Who among them had not spent many a night for the past four years under a mosquito net in tropical and sub-tropical heat? Who was still not cursing the day when he experienced his first monsoon in a canvas tent at the base of a mountain or his neighbor's vomit on the high seas? No, the common impediments to communication that we often hear Japanese and non-Japanese cite today were not those of the occupying troops and their occupied hosts.

It was surely not a question of Japanese being too difficult a language難しい言葉 for foreigners to learn. The common impediments to communication that we often hear Japanese and non-Japanese cite today, were surely not those of the occupying troops and their occupied hosts. Nor, did it likely have anything to do with the hidden qualities of a mysterious culture不思議な社会 shrouded in contradictions. Neither, was it a matter of Japan being an island nation島国, suspicious of the outside world, and reluctant to communicate with non-Japanese for a lack of oral competence in the English language. No, Japan had just spent the past 60 years educating itself and much of East Asia about how to beat the Western world at its own game. To believe that this new knowledge had been imparted by Japanese to anyone in a language other than Japanese is simply incredible. The reported acts of cultural genocide that took place during Japan's late 19th and early 20th century annexation日本統治時代 of the Korean peninsula朝鮮半島 suggest a very different pattern.

Indeed, how Japan acquired new technology for itself and how it passed it on to others were surely two very different phenomena.

In the end, however, we are all human beings, and the languages, cultures, and events that bind and separate us often do more to disguise than reveal what we share in common. In short, if there is a desire to communicate, we can always find a way to do so. Realistically, however, most everyone either had an awful desire to return home or wished those who had the desire would finally be permitted to do so. Important is that the occupation lasted for half a decade, and one can easily tire of guard duty. Surely, the Japanese had had their hands full with reconstruction -- well, at least, those who had the means to reconstruct.

communication: motivation and mode

The presence of US and allied troops on Japanese soil was not exactly a grand opportunity for Japanese and non-Japanese to come together and engage in English conversation英会話 classes. Nor, was there likely very much need on the part of most US servicemen to learn the language of their vanquished enemy. Armed personnel do not require much communication to navigate their way through crowded unarmed streets, and courting sexual gratification through a neighborhood pimp at a local bar required little in the way of delicate negotiation skills. At the time, one simply presented some good that could be easily supplied and was highly desired, and the door to physical bliss would open. Shall we ignore the hidden STD that so often was a part of the exchange?

In contrast, there were very few people within the US military that knew any Japanese, and there was a tremendous need on the part of GHQ-SCAPGeneral Headquarters, Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers and other foreign observers for bilingual people to translate government documents, follow the local press, and interpret just what it was that everyone was actually monitoring or observing. Accordingly, it is difficult to monitor what you do not understand, and the observation of social behavior in the absence of knowledge of the language and culture that gudies and triggers the behavior is unlikely to prove very useful. Furthermore, the Eighth Army must have grown frustrated with armed force as the only method they had at their disposal to enforce physical compliance when the need was present. Even in trading with a pimp, a little bit of bilingual verbal communication could liklely go along way in the lubrication of desired, as opposed to unwanted friction.

Despite the obvious demand for bilingualism on the non-Japanese side, there was little or no supply that did not come from the Japanese side. Even there, however, bilingual resources were scarce. Once again, the United States was only one of many players in the region, and Japan's trade with Great Britain and North America was nearly always for large ticket items that were infrequent and did not require a large translation staff to carry out. Although one can imagine Japanese industrialists extending their own bilingual staff in order to obtain special treatment from GHQ, these limited commercial exchanges would hardly be adequate to meet the daily bilingual needs of the GHQ.

In another important light, translation and interpretion are not the two-way street that many commonly expect. Translating or interpeting from someone else's language into your own is not the same as translating or interpeting your own language into someone else's. As good bilingualism -- if it were to be found at all -- nearly always came from the Japanese side, one can readily surmise that the Japanese were much better at understanding their unwanted guests, than the Occupation was at understanding their reluctant host. Moreover, effective communication requires a reliable feedback mechanism, and few Japanese were on the US payroll.

Once again, the Japanese could cooperate where they found it convenient to do so, and demur, reinterpret, and obfuscate where they found it counterproductive to their own objectives.

When you hit a donkey with a stick, it knows where you do not want it to go, but the direction that it takes to get away is its own. As a military force the US occupation was well-versed in the application of negative incentives. What it lacked, however, was important knowledge about the provision of carefully constructed positive incentives. This lack of knowledge was compounded by the absence of familiarity with Japanese culture and society. In fact, the single most important positive incentive that the US military could offer was its timely departure, and it was surely this that the Japanese focused on.

Furthermore, as a top-down operation, the eyes and ears of military commanders are less focused on those whom they lead, than they are on the achievement of their objectives. In wartime rank and file military personnel are pretty much a captive work force, Furthermore, the military's intelligence operations are focused on matters of security and the maintenance of authority. Listening to the needs of the Japanese people, either directly from the Japanese people themselves, or indirectly from the soldiers that interacted with the Japanese on a daily basis, was surely not a terribly important concern -- unless, of course, it affected GHQ's public image.

In the end, the primary source of demand for communication between the two sides must have come from the Japanese side. As we have already noted, the Japanese economy was in dire straits, and many Japanese were in need of essential commodities. The most obvious and ready source for those commodities was the American G.I., who generally had far better access to what many Japanese wanted than most Japanese. This said, how many philanthropists does one find in a military establishment where merit and rank are the name of the game. In contrast, there must have been many a bored US serviceman who, although happy that the war had ended, was in search of new sources of action. Japan was rich in culture and geography, and human want is a strong motivator for the creation of any market.

As in any crisis, when there is an extreme shortage of a basic necessity, prices rise, and only the wealthy, criminal, shrewd, hardy, and very lucky survive. Japan was no exception in this regard. Despite a concerted effort on the part of the Japanese government to reign in the prices of basic necessities through rationing programs, black markets sprang up everwhere. An important segment of this black market activity included members of the American military. On the Japanese side, basic necessities and luxury items were the primary items sought after. On the American side entertainment and Japanese souvenirs were the coveted items. In order to make this market work a lingua franca was necessary, and English and Japanese were the only two languages that were very abundant. Although either language could have functioned in the capacity of a lingua franca, and probably did in many cases, English was clearly more available on the Japanese side, and Japanese was all but absent on the US side. However, abundance and availability could hardly have been the only factors that came into play in determining which language one used to negotiate a trade.

Up until the war Japan was the only super power in East Asia that was truly asian, and as a result it was barely known in the West. There were few university departments in the United States that offered coursework in the Japanese language, and US-Japanese residents tended to huddle in close communities like many of their other overseas East Asian counterparts. Thus, there were few books available that were designed for native English learners of the Japanese language. In contrast, though not widespread English was considered one of Japan's several important foreign languages and, as a result, had been taught in Japan's most prestigious universities and in several of Japan's better public and private secondary schools. Thus, there were English language textbooks available in Japan's larger cities, if only in small number.

Another important factor that must have encouraged English as the lingua franca of Japan's occupation was collective psychology. Among the conquerors pride of conquest and pity were surely the initial prevailing sentiments; among the conquered fear and alienation must have been very prevalent. Under such circumstances English would be the preferred language for both sides, as it would appease the wanton among the conquerors and restore confidence in the insecure and alienated of the conquered. Moreover, the future was clearly uncertain for many, and the immediate was pressing on one, if not, both sides.

Finally, if we can agree that English was the obvious choice for Japan's postwar lingua franca, than we have only to imagine how and where it was acquired.

Would the likeliest of places not have been along Japan's erotic urban and exotic rural landscapes, in the tiny, but newly flourishing Christian communities, and on the perimeter of Tōkyō's newly expanding international communities?

the social landscape of occupation

Put yourself in the position of a Japanese woman desirous of food, clothing, and any number of other commodities that were denied her for nearly a decade while the war was still waging in the Asian Pacific. You could be a single mother whose husband was lost in the war, the head of a family with many mouths to feed, a desperate single with few friends and no real source of income, an adventurous youth curious about American conquest, a Japanese patriot who was grateful for the opportunity to serve her nation, or simply a woman of some talent who liked being with men. Important was that you lived close to a place where the Japanese Ministry of Interior内務省警保局 knew that American troops would be stationed and that you passed by your local police box and/or read the local newspaper. For, it was in these places where local Japanese governments advertised for participants接待婦の募集 in Japan's nationwide association for amusement and recreation (RAA特殊慰安施設協会). No matter your situation, you knew of a place where you or another female family member could obtain shelter, a source of income, or a cash advance in exchange for sex with young, virile, US servicemen. Would it be worth learning a little English? Would it be worth catching an STD, if you even knew what one was? Indeed, there was about a 50 percent chance that you even knew that sexual favors would be exchanged before you signed up for the program.

Maybe you had caught the eye of an adventurous serviceman who, tired of war and disgusted with the ignoble spirit that brings it about, was seeking a fresh start. Imagine, too, that your father had just returned home with 5.5 million other Japanese expatriates driven from their overseas assignments by the humiliation of defeat. Unlike most of these, however, your father spoke English with some degree of fluency and had a better idea about where Japan's future was headed. Your father understood, for example, that there would be no turning back, and that Japan's future lay in its unusual, but now inexorable wedlock with the United States. Further say, that your new American boyfriend had clearly demonstrated his enchantment with the Japanese way of life and his readiness to remain in Japan after his tour of duty was completed. Finally, imagine that your father saw in your boyfriend an opportunity to teach other Japanese English. Would you teach your boyfriend Japanese? Would you have the strength to follow your father's wishes and marry him?

Maybe you were a young Tōkyōite who worked in a Japanese trading house that survived the war. One day you were told by your boss that new trading opportunities would soon be opening in the United States. At about the same time a former schoolmate同窓生 told you that his bar居酒屋 was now located close to an American military base米軍基地. While speaking with your buddy one evening you learn that his business has picked up dramatically as a result of the change, but that he is having trouble handling his new clientèle, because he does not know their language. In this conversation you discover an opportunity to help yourself, your friend, and your company, enroll in a private language school, and frequent your friends bar as often as you can to acquire English language conversation skills.

Finally, perhaps you were a smart girl who had been lucky enough to attend a junior high school and whose older brother兄 had been hired by the military to clear and pave a road leading up to a nearby base. One day, you accompany your brother to his work place, and are unexpectedly greeted by your brother's boss outside the gate. After this meeting your brother and his boss get to talking in the presence of a co-worker who is a little bilingual. Several days later your brother asks you to prepare an extra setting for hanami花見 in Ueno Park上野公園. It is spring and the sakura桜 are in full bloom満開. It is a festive occasion, and you know that could you acquire a little English from your brother's boss, you could also meet GIs with your friends in front of the Tōkyō PX in Ginza銀座 -- the former Matsuya松屋. As this would enable you to obtain highly desired contraband with no sexual commitment, you energetically prepare an extra setting, please your brother and his boss, and obtain your contraband.

Unlike the girl above, you had never attended secondary school, but you were an enegetic teen with good street smarts. You understood, for example, that a little English could go along way in attracting US serviceman into your embrace. You were young and attractive and sex would be an easy way to obtain just about anything you wanted. Besides, you lived very close to Shinjuku新宿 and did not have to become anybody's slave to engage in the district's sex trade. So, you meet with your friends and decide to try it out. You keep close company with each other and stay clear of places like Yoshiwara. Other's become envious of your wealth, and their thoughts run wild. You are modest, say little, and enjoy your life. Your English improves, and somehow you escape an incurable disease, or do you?

No matter the scenario, with a quarter million US troops scattered across a society in which nearly anything and everything eventually finds a proper place, the English languageバイバイ and the Japanese economy売買 were reunited in mutually exploitative wedlock売春, and Japanese society began its postwar rebirth.

american housewives, the christian church, and the associated press

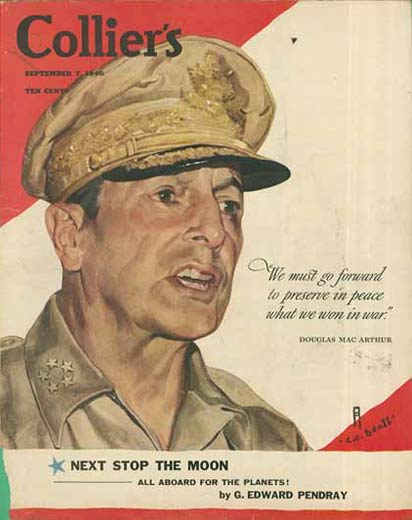

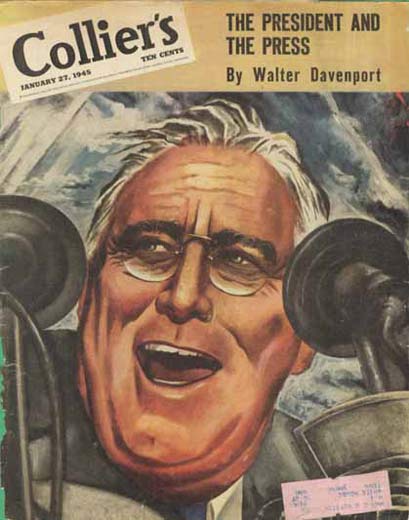

Although the world must have taken a sincere interest in Japan at the war's end, one's fascination with the fallen empire was probably limited to damage assessment, the after affects of two atomic bombs, troop-life, the war trials, measures taken by General MacArthur to insure that Japan would never again become a threat to the United States and, of course, General MacArthurマッカーサー himself.

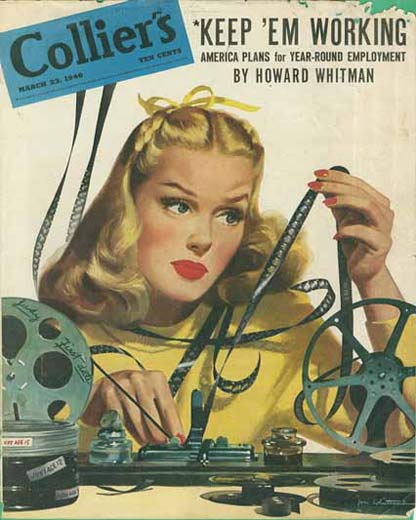

In this context only troop-life and General MacArthur appear very important, because it was at the request of General MacArthur that the two second largest waves of native English language speakers were brought to the Japanese archipelago -- the housewives and families of US servicemen and the Christian church. Although the reasons for this were likely many, the primary reason appears to be the very high rate of venereal disease reported among US servicemen during the occupation -- well over a quarter of all US military personnel stationed in Japan eventually suffered from some sort of STD. Another important reason may have been post-war labor unrest among American women and political reputation.

During the war the American female filled many of the industrial jobs that would otherwise have been filled by the American male who was fighting overseas. After the war the US male population returned home and reclaimed its rightful position in the American work force. Not every woman, however, was ready to relinquish her newly one independence as a paid member of society. This surely created important social friction that could be relieved, in part, by allowing married women to join their male counterparts overseas.

Furthermore, it must have been pretty embarrassing for General MacArthur when he was informed that a quarter of his troops were infected by an STD and that this infection occurred under his watch. Had these goings-on found their way into the mainstream American press, MacArthur's carefully cultivated hero-image would have suffered. So, in addition to inviting the wives and families of American military personnel to join their spouses stationed in Japan, General MacArthur placed the Japanese government's newly established recreational and amusement red-line districts赤線区域 off-limits to American military personnel. As a further precaution, MacArthur invited the Christian church. In 1950 General MacArthur is quoted as saying,

- I have publicly stated my firm belief that Christianity offers to Japanese a sure and stable foundation on which to build a democratic nation. Japanese are becoming increasingly aware of fundamental values of Christian religion and appreciative of its spiritual and moral blessing.

- For the rehabilitation of Japan, there must be a revival of the spirit, if we are to save the flesh.

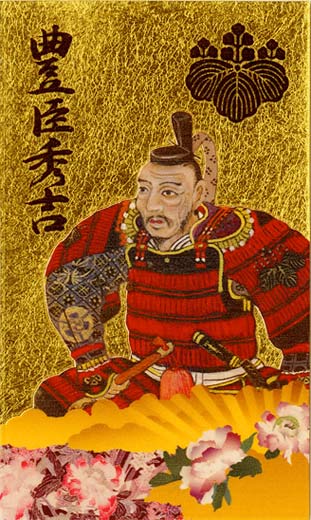

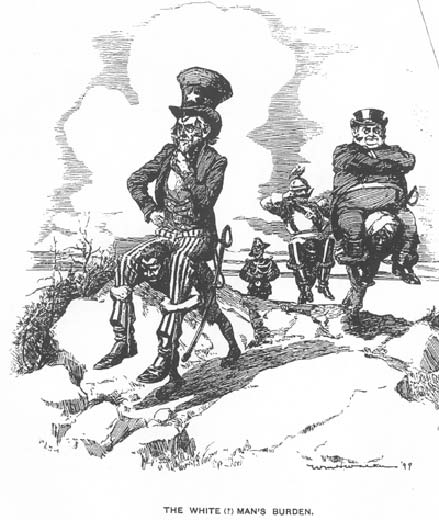

By encouraging the presence of the Christian church General MacArthur was able to defer blame from his own troops to the Japanese and temporarily divert attention away from the Japanese emperor. In addition, he was able to evoke sympathy on the home front where the notion of Rudyard Kipling's white man's burden continues to hold important sway in America's highest political circles. Finally, many in the world's Christian community saw a grand opportunity to reestablish itself in Japan after two and a half centuries of persecution and the subsequent politicization of the Shintō faith神道 under the Meiji emperor明治天皇. Indeed, at no better time since the landing of Francis Xavier in 1549 did the Christian church have a chance to deepen and spread its roots in Japan, and with MacArthur at the helm of Japanese society there would be no Toyotomi Hideyoshi豊臣秀吉 to get in their way.

Between 1947 and 1951 some 5,000 Christian missionaries arrived in Japan -- a number far larger than the approximately 800 missionaries that were compelled to leave Japan during the war. Few of these new missionaries were very knowledgeable of Japan let alone the Japanese language, and most depended on Japanese interpreters to get their message across. Many of the them were expatriate refugees from the Chinese mainland.

As a result of MacArthur's initial effort to win over the minds of Japanese society, Japan's second elected, postwar, prime minister, Katayama Tetsu, was a professed Christian. It is also said that Yoshida Shigeru, Japan's first elected, postwar prime minister, was baptised on his deathbed and buried as a Christian. Evidence for this is the location of his funeral ceremony and his place of burial. After being honored at St. Mary's Cathedral東京カテドラル聖マリア大聖堂 in Tōkyō東京 the prime minister was buried in Tōkyō's Aoyama Cemetery青山霊園. Yoshida Shigeru was one of Japan's longest running prime ministers and is responsible for the foundation of Japan's current diplomatic and military alliance with the United States -- the Yoshida Doctrine吉田主義. In contrast, Prime Minister Katayama's time in office was very short; his socialist politics put him at odds with MacArthur's anti-communist convictions and the Japanese government's effort to appease the occupation. With the onset of the Cold War冷戦, religion and democracy soon gave way to politics and economics. Christianity quickly resumed its status as a minority religion. However, its role as a conduit for English language conversation practice remains strong up to this day, as many Christian churches cater to the resident foreign community and the Christian church is a popular place among young Japanese to marryウァイト・ウエディング.

In addition to the sudden infusion of military spouses and the clergy, there must have been a large number of English speaking foreign correspondents eager to report about the state of the conquered enemy. This sudden infusion of new demand for bilingual speakers in an already very tight language market would have resulted in biased reporting. The reasons for this are several.

Firstly, the military would have had priority over the most capable bilingual Japanese willing to serve Western interests. Secondly, the number of well-informed, pro-Western expatriots was likely small, as their presence would have been discouraged during the war. Thirdly, those Japanese both capable and willing to serve as bilingual informants would have had their own political agendas dominated by Japanese expatriots who had just returned from overseas commercial and diplomatic outposts, by local observers who made it their business to observe and interpret the West for interested Japanese politicians and business people, and by Japanese pacifists whose voices had been suppressed during the war. Finally, even if the information that was received were accurate, what was reported or not reported was subject to the censorship of GHQ.

This means that the information received from Japanese informants could not be easily confirmed or disconfirmed and that much of the information reported by foreign correspondents would have been limited to that obtained from the US military and Japanese with a pro-American, pacifistic, or protective national agenda.

for

for

summary and conclusion

In summary, the immediate postwar period as viewed from a cultural and linguistic perspective can be divided into two major, sometimes conflicting, sometimes overlapping movements: one, placate the US government and thus minimize its intrusion into Japanese domestic affairs; and two, nurture, as well as one was able, whatever friendship with the United States government was possible. Let us now try to imagine how these two movements likely played themselves out against one another.

![]() In his address to the Japanese people on 14 August 1945 Emperor Hirohito expressed his regret about Japan's failure to ward off the inevitable and asked his people to make every effort to move forward in a spirit of peace and cooperation. For in the end, the imperial state had been preserved, and Japan's failed, but well-meant intentions would not be in vain. Japan would rise again -- a nation of world peace and prosperity.

In his address to the Japanese people on 14 August 1945 Emperor Hirohito expressed his regret about Japan's failure to ward off the inevitable and asked his people to make every effort to move forward in a spirit of peace and cooperation. For in the end, the imperial state had been preserved, and Japan's failed, but well-meant intentions would not be in vain. Japan would rise again -- a nation of world peace and prosperity.

Source: National Diet Library国立公文書館. 2003-2004. The Birth of the Japanese Constitution日本国憲法の誕生. The End of the War and the Beginning of Constitutional Revision戦争終結と憲法改正の始動. Documents and Interpretation資料と解説. 1-7 Declaration of Peace終戦の詔書. 14 August 1945昭和20年8月14日. [online document / reserve]

![]() In 1946 the average age of the Japanese male and female was 42.8 and 51.1 years, respectively. By 1951 the average age of the Japanese male increased to 61, and that of the Japanese female to 64.

In 1946 the average age of the Japanese male and female was 42.8 and 51.1 years, respectively. By 1951 the average age of the Japanese male increased to 61, and that of the Japanese female to 64.

Though the likely cause for the large difference in the lifespan of the average Japanese male and female in 1946 was many years of war, the important differences between 1946 and 1951 -- a 43 and 25 percent increase in the life-span of the average Japanese male and female, respectively -- was more likely attributable to the better health and nutritional care received by the Japanese public during the occupation.

Source: Tsurumi Shunsuke鶴見俊輔. 1980. The History of Popular Culture in Postwar Japan戦後日本大衆文化史, 1945 to 1980. Iwanami Shoten岩波書店, p. 21.

![]() The Portuguese are the first recorded Westerners to have set foot on Japanese soil. They arrived in Japan in 1543 after a vicious storm wrecked their ship at sea. Shortly after their arrival they established a tiny Portuguese community on Shūshi Island種子島. This humble and fortuitous beginning was followed several years later by the arrival of Francis Xavier in Kagoshima鹿児島 in 1549 and the second arrival of a Portuguese ship off the shore of Shūshi Island in 1550. From these events arose a thriving colony of Western traders that has persisted today. Among the many historical firsts of Portugal's relationship with the Japanese include the introduction of firearms and Christianity, and Japan's first overseas emissaries天正遣欧少年使節 to Europe.

The Portuguese are the first recorded Westerners to have set foot on Japanese soil. They arrived in Japan in 1543 after a vicious storm wrecked their ship at sea. Shortly after their arrival they established a tiny Portuguese community on Shūshi Island種子島. This humble and fortuitous beginning was followed several years later by the arrival of Francis Xavier in Kagoshima鹿児島 in 1549 and the second arrival of a Portuguese ship off the shore of Shūshi Island in 1550. From these events arose a thriving colony of Western traders that has persisted today. Among the many historical firsts of Portugal's relationship with the Japanese include the introduction of firearms and Christianity, and Japan's first overseas emissaries天正遣欧少年使節 to Europe.

Source: City of Nagasaki長崎市, Japan. 2002. The History of Deshima出島ヒストリー. The Birth of Deshma and Barbarian Trade出島の誕生と南蛮貿易. [online document | reserve] (downloaded on 12 October 2009).

![]() The Iwakura Mission岩倉遣外使節団 was only one of many diplomatic and scientific missions dispatched by the Meiji明治 government to obtain knowledge from the West. This particular mission was led by Japan's ambassador特命全権大使, Iwakura Tomomi岩倉具視 and chronicled by Itō Hirobumi伊藤博文, one of three deputy ambassadors副史 to the mission. The journey lasted for two years and had as its two primary objectives: the renegotiation of the so-called unequal treaties日米和親条約 and information gathering. Due to its size, participants, and well-documented history it is probably the most celebrated mission of the period.

The Iwakura Mission岩倉遣外使節団 was only one of many diplomatic and scientific missions dispatched by the Meiji明治 government to obtain knowledge from the West. This particular mission was led by Japan's ambassador特命全権大使, Iwakura Tomomi岩倉具視 and chronicled by Itō Hirobumi伊藤博文, one of three deputy ambassadors副史 to the mission. The journey lasted for two years and had as its two primary objectives: the renegotiation of the so-called unequal treaties日米和親条約 and information gathering. Due to its size, participants, and well-documented history it is probably the most celebrated mission of the period.

Sources

- National Diet Library国立国会図書館. Modern Japan in Archives史料にみる日本の近代. Modern Japan from the first arrival of Commodore Perry to the signing of the San Francisco Peace Treaty開国から講話まで100年の軌跡. Chapter 1.7 - Towards a Constitutional State立憲政治への試み. The Iwakura Mission岩倉遣外使節団. [online document | reserve] Downloaded on 10 October 2009.

- ibid. Itō Hirobumi伊藤博文. 1871明治4年. Photographic image of Deputy Ambassador Itō's handwritten diary. [online document | reserve].

![]() Despite Japan's initial attraction to the US banking system discussions between Japan's Finance Minister, Matsukata Masayoshi松方正義 and France's Finance Minister and noted 19th century economist, Léon Say, in 1878 led Japan away from the US model. These discussions and what followed appear to have left an enduring mark on Japan's financial system. Even today, whereas the Bank of Japan follows a largely Western demand-side approach to Japan's macroeconomy, the Ministry of Finance adhere's to a more traditional, French-style, supply-side approach.

Despite Japan's initial attraction to the US banking system discussions between Japan's Finance Minister, Matsukata Masayoshi松方正義 and France's Finance Minister and noted 19th century economist, Léon Say, in 1878 led Japan away from the US model. These discussions and what followed appear to have left an enduring mark on Japan's financial system. Even today, whereas the Bank of Japan follows a largely Western demand-side approach to Japan's macroeconomy, the Ministry of Finance adhere's to a more traditional, French-style, supply-side approach.

Source: Simon J. Blytheway and Michael Schulz. 2009. The Dynamics of Wakōn Yōsai和魂洋才. The paradoxes and challenges of financial policy in an industrializing Japan, 1854-1939. In People, Place and Power: Australia and the Asia Pacific. Black Swan Press. pp. 61.

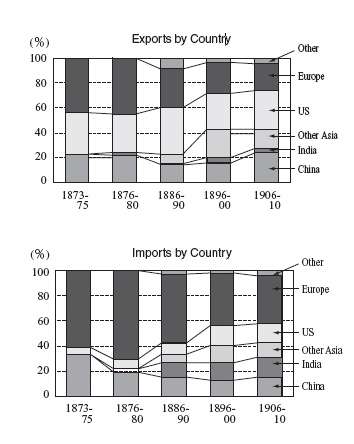

![]() Between 1873 and 1910, nearly the entirety of the Meiji Reformation, trade with the United States never accounted for more than 20 and 40 percent of Japan's imports and exports, respectively. Japan's primary source of manufactured imports was Europe, and its primary exports to the United States were silk and tea. When WWI broke out Europe could no longer satisfy East Asia's demand for imported manufactured products; Japan filled the vacuum with Japanese produced goods. This increase in overseas demand stimulated Japanese domestic production and its desire for Western technology. After the war Japan invited both European and US firms to invest in Japan's ever growing economy. Many accepted.

Between 1873 and 1910, nearly the entirety of the Meiji Reformation, trade with the United States never accounted for more than 20 and 40 percent of Japan's imports and exports, respectively. Japan's primary source of manufactured imports was Europe, and its primary exports to the United States were silk and tea. When WWI broke out Europe could no longer satisfy East Asia's demand for imported manufactured products; Japan filled the vacuum with Japanese produced goods. This increase in overseas demand stimulated Japanese domestic production and its desire for Western technology. After the war Japan invited both European and US firms to invest in Japan's ever growing economy. Many accepted.

Source: Ohno Kenichi大野健一. 2006. The Economic Development of Japan: The Path Traveled by Japan as a Developing Country. Chapter 4, Importing and Absorbing Technology. [online document / reserve] Tōkyō: GRIPS Development Forum.

![]() During the first part of the 20th century Great Britain and Japan maintained close military and economic ties that were of important concern to the United States, Australia, and New Zealand who were fearful of Japanese domination in the Western Pacific.

During the first part of the 20th century Great Britain and Japan maintained close military and economic ties that were of important concern to the United States, Australia, and New Zealand who were fearful of Japanese domination in the Western Pacific.

Source: Phillips Payson. O'Brien, Editor. 2004. The Anglo-Japanese Alliance 1902-1922. [online document] Routledge.

![]() In an apparent effort to stabilize conflicting colonial claims in the Western Pacific that had arisen during World War I, the United States, Great Britain, France, and Japan signed the Four Powers On Insular Possessions Treaty in 1921; this treaty ended the bilateral Anglo-Japanese Alliance. Shortly thereafter, two more treaties were signed including the Five Powers Naval Disarmament Treaty and the Nine Power Treaty that effectively placed the United States Navy on par with the British Navy in the region and diminished Japan's influence. It is likely no coincidence that all three of these treaties excluded Russia where the Communists had already taken hold.

In an apparent effort to stabilize conflicting colonial claims in the Western Pacific that had arisen during World War I, the United States, Great Britain, France, and Japan signed the Four Powers On Insular Possessions Treaty in 1921; this treaty ended the bilateral Anglo-Japanese Alliance. Shortly thereafter, two more treaties were signed including the Five Powers Naval Disarmament Treaty and the Nine Power Treaty that effectively placed the United States Navy on par with the British Navy in the region and diminished Japan's influence. It is likely no coincidence that all three of these treaties excluded Russia where the Communists had already taken hold.

Source: Ronald E. Dolan and Robert L. Worden, Editors. 1994. Japan: A Country Study. Diplomacy. Washington: US Government Printing Office for the Library of Congress. [online document / reserve]

![]() Within about a half-century after the arrival of Francis Xavier in the 16th century the Christian church of Japan ran aground. Christianity was viewed by Toyotomi Hideyoshi豊臣秀吉 as an obstacle in his bid for a unified Japan. By 1600 many Christians -- Japanese and foreigners, alike -- had fled japan, and those that remained spent the next three hundred years in near total isolation from their fellow countrymen. It was this anti-Christian movement that eventually led to the formation of the Dutch colony of Deshima出島 -- Japan's only door to the outside world under the Tokugawa Bakfu徳川幕府.

Within about a half-century after the arrival of Francis Xavier in the 16th century the Christian church of Japan ran aground. Christianity was viewed by Toyotomi Hideyoshi豊臣秀吉 as an obstacle in his bid for a unified Japan. By 1600 many Christians -- Japanese and foreigners, alike -- had fled japan, and those that remained spent the next three hundred years in near total isolation from their fellow countrymen. It was this anti-Christian movement that eventually led to the formation of the Dutch colony of Deshima出島 -- Japan's only door to the outside world under the Tokugawa Bakfu徳川幕府.

Sources:

- Catholic Online. Saints and Angels. St. Paul Miki [online document | reserve] (downloaded on 14 October 2009).

- op. cit. City of Nagasaki. 2002.

![]() When President Obama met the Saudi King for the first time he clearly bowed. Not only did this cause an uproar in the US Senate, but it compelled the White House to excuse the President's behavior through a statement of denial.

When President Obama met the Saudi King for the first time he clearly bowed. Not only did this cause an uproar in the US Senate, but it compelled the White House to excuse the President's behavior through a statement of denial.

Sources:

- Alex Spillius. 2009. "Barack Obama criticised for 'bowing' to King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia". [online document | reserve] The Telegraph, April 9th. (downloaded on 14 October 2009).

- The Washington Times. 2009 Editorial: "Barack takes a bow". [online document | reserve] (downloaded on 14 October 2009.

- YouTube. 2009. Obama bows to Saudi King. [online document] (downloaded on 14 October 2009).

![]() In her presentation entitled "Cultural Genocide and the Japanese Occupation of Korea「文化ジェノサイド」と日本の朝鮮支配" Matsumura Yūko松村裕子 states that the Japanese sought to prohibit the use of Korea's native tongue, renamed the people and places of Korea, removed Koreans from institutions of higher education, destroyed Korea's cultural artifacts, denied Koreans basic religious freedoms, and reformed the Korean system of education. In so doing she maintains that the Japanese sought to rob Koreans of their national identity and to destroy their traditional family system. Even Japan's refusal to recognize Korea as a Japanese colony was an attempt to squelch Korean society as very different from Japan itself.

In her presentation entitled "Cultural Genocide and the Japanese Occupation of Korea「文化ジェノサイド」と日本の朝鮮支配" Matsumura Yūko松村裕子 states that the Japanese sought to prohibit the use of Korea's native tongue, renamed the people and places of Korea, removed Koreans from institutions of higher education, destroyed Korea's cultural artifacts, denied Koreans basic religious freedoms, and reformed the Korean system of education. In so doing she maintains that the Japanese sought to rob Koreans of their national identity and to destroy their traditional family system. Even Japan's refusal to recognize Korea as a Japanese colony was an attempt to squelch Korean society as very different from Japan itself.

Source: Matsumura Yūko松村裕子. 2004. Cultural Genocide and the Japanese Occuaption of Korea. Comparative Genocide Studiesジェノサイド論の系譜, 1st Workshop. University of Tōkyō東京大学. [online document / reserve]

![]() As a student of Western culture Japan acquired this knowledge through limited interaction with foreign traders on Japanese soil, the employment of foreign experts from a variety of countries, and through direct observation by Japanese who had been dispatched overseas to gather information. At the time, French was still the lingua franca of world diplomacy, and no single language dominated the world of science. The Portuguese and the Dutch were surely the oldest, resident, foreign populations in Japan, but their interaction with the local population was severely limited by the creation of the Deshima出島 trading community. Moreover, Japan's invited scholars came from a variety of different European countries and North America. Each scholar lectured in his own language that was assiduously acquired by his students, for it was only in this way that these latter could access the recommended scientifc literature of their foreign mentor. Moreover, educational and diplomatic missions to Europe and North America were likely populated by bilingual Japanese representing a variety of different languages and levels of linguistic competence. Among the members of these missions observation was surely the primary means of acquisition.

As a student of Western culture Japan acquired this knowledge through limited interaction with foreign traders on Japanese soil, the employment of foreign experts from a variety of countries, and through direct observation by Japanese who had been dispatched overseas to gather information. At the time, French was still the lingua franca of world diplomacy, and no single language dominated the world of science. The Portuguese and the Dutch were surely the oldest, resident, foreign populations in Japan, but their interaction with the local population was severely limited by the creation of the Deshima出島 trading community. Moreover, Japan's invited scholars came from a variety of different European countries and North America. Each scholar lectured in his own language that was assiduously acquired by his students, for it was only in this way that these latter could access the recommended scientifc literature of their foreign mentor. Moreover, educational and diplomatic missions to Europe and North America were likely populated by bilingual Japanese representing a variety of different languages and levels of linguistic competence. Among the members of these missions observation was surely the primary means of acquisition.

![]() A social science researcher in a modest Division of the least ranking Section of the SCAP organization once remarked:

A social science researcher in a modest Division of the least ranking Section of the SCAP organization once remarked:

- From the beginning of the Occupation various informal or semiofficial organizations had been assigned the job of collecting information on the many reforms the Japanese were guided to undertake by the Occupation.... This collection of data was necessary because of the language barrier, since while Japanese sources of information were relatively abundant, very few Americans could read Japanese well enough to use these sources in their original form, and obtaining translations was a constant problem.

Source: John W. Bennett and Ishino Iwao. 1963. Paternalism and the Japanese Economy: Anthropological Studies of Oyabun親分-Koyabun子分 Patterns. University of Minnesota Press. Obtained from Doing Photography and Social Research in the Allied Occupation of Japan, 1948-1951: A Personal and Professional Memoir. Chapter 1 Social Research in a Military Occupation. [online document | reserve] (downloaded on 16 October 2009).

![]() In still another remark made by a researcher in the Public Opinion and Social Research Division of the Civil Information and Education Section of the SCAP command one learns that good follow-up was often either impossible or not attempted.

In still another remark made by a researcher in the Public Opinion and Social Research Division of the Civil Information and Education Section of the SCAP command one learns that good follow-up was often either impossible or not attempted.

- Numerous reforms seemed to fan out over the surface and vanish; others had unexpected results; and in almost all cases, Americans in "command" positions had difficult determining just who had the responsibility in Japanese organizations.

Source: Ibid. Bennet and Ishino.

![]() A movement to abolish English language instruction in Japanese public schools had already started during the Taishō大正 era. By 1931 (Shōwa 6昭和6年) the number of hours of English language instruction in Japanese classrooms was finally reduced. The anti-English language movement climaxed in 1942 (Shōwa 17昭和17年) when all US and UK instructors were banned from Japanese universities.

A movement to abolish English language instruction in Japanese public schools had already started during the Taishō大正 era. By 1931 (Shōwa 6昭和6年) the number of hours of English language instruction in Japanese classrooms was finally reduced. The anti-English language movement climaxed in 1942 (Shōwa 17昭和17年) when all US and UK instructors were banned from Japanese universities.

Source: Imura Motomichi伊村元道. 2003. Japan's Two Centuries of English Language Instruction日本の英語教育200年. Tōkyō東京: Taishūkan Shoten大修館書店, p. 189.

![]() When the Nagoya International Club for Elite Entertainment国際高級享楽ナゴヤクラブ was formed in Aichi Prefecture愛知県, a survey was conducted by the local authorities. In the survey it was discovered that only 52 percent of those interviewed understood that they were being recruited for the purpose of performing sexual favors.

When the Nagoya International Club for Elite Entertainment国際高級享楽ナゴヤクラブ was formed in Aichi Prefecture愛知県, a survey was conducted by the local authorities. In the survey it was discovered that only 52 percent of those interviewed understood that they were being recruited for the purpose of performing sexual favors.

Source: Kawashima Takane川島高峰. 1998. "Psychology of the Occupied被占領心理: The Bureaucratic Rationale Behind Japan's Recreation and Amusement Association (RAA)肉体の戦士と官僚的「合理性」" [online document | reserve] In Currents and Contours of Japanese Thought日本思想の地平と水脈. Section 5 The RAA第5節 特集慰安施設. The Recruitment of Female Entertainers.接待婦の募集 Japan: Periskanshaペリかん社.

![]() Yoshiwara吉原 is an old Tōkyō city district that was put off-limits to US GIs during the occupation. It was well known as a red-light district赤線区域 and famous for its established houses of prostitution売春.

Yoshiwara吉原 is an old Tōkyō city district that was put off-limits to US GIs during the occupation. It was well known as a red-light district赤線区域 and famous for its established houses of prostitution売春.

Source: op. cit. John W. Bennet. Women of the Night. Japan and the Allied Occupation. [online document | reserve] (downloaded on 22 October 2009).

![]() There is probably no country in the world in which sexual prostitution is not legitimized, at least in part, by the laws and customs of that country. Japan is, of course, no exception in this regard. In a similar light, there is probably no military in the world whose command is not confronted with civil complaints related to this kind of behavior. With the presence of between 150,000 and 300,000 US troops spread across the Japanese archipelago during the occupation the Japanese sex industry flourished. So rampant was the sex trade that one out of every for US servicemen suffered from some form of sexually transmitted disease -- this despite explicit orders from GHQ not to engage in prostitution.

There is probably no country in the world in which sexual prostitution is not legitimized, at least in part, by the laws and customs of that country. Japan is, of course, no exception in this regard. In a similar light, there is probably no military in the world whose command is not confronted with civil complaints related to this kind of behavior. With the presence of between 150,000 and 300,000 US troops spread across the Japanese archipelago during the occupation the Japanese sex industry flourished. So rampant was the sex trade that one out of every for US servicemen suffered from some form of sexually transmitted disease -- this despite explicit orders from GHQ not to engage in prostitution.

Sources:

- Holly Sanders. 2006. "Indentured servitude and the abolition of prositution in postwar Japan". Program on US-Japan Relations, Harvard University. [online document | reserve] USJP Occasional Paper 06-11, pp. 26-28. (downloaded on 16 October 2009).

- Alfred C. Oppler. 1976. Legal Reform in Occupied Japan: A participant looks back. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 157-58.

- Gregory M. Pflugfelder. 1999. Cartographies of desire: male-male sexuality in Japanese discourse, 1600-1950. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, p. 329-30.

![]() This word rebirth could be misleading in this context, as the same bureaucracy that was in place during the war remained largely in place after the war. In fact, the policy of using comfort women慰安婦 to placate the forces of occupation at home, was very similar to the one used by the Japanese military overseas. If there was an important difference, then it was only that Japanese women慰安婦 were conscripted for the forces of occupation, and non-Japanese women従軍慰安婦 were conscripted for Japan's imperial army.

This word rebirth could be misleading in this context, as the same bureaucracy that was in place during the war remained largely in place after the war. In fact, the policy of using comfort women慰安婦 to placate the forces of occupation at home, was very similar to the one used by the Japanese military overseas. If there was an important difference, then it was only that Japanese women慰安婦 were conscripted for the forces of occupation, and non-Japanese women従軍慰安婦 were conscripted for Japan's imperial army.

Source: op. cit. Kawashima Takane川島高峰. 1998. Section 5 The RAA第5節 特集慰安施設. Functional Operations運営の実際.

![]() Christian missionaries very familiar with Japanese society expressed important doubt about the postwar future of the Christian church in Japan. Accordingly the vast majority of post-war missionaries were new to Japan. These two facts suggest strongly that MacArthur was poorly informed about Japanese society, was philosophically arrogant, or was indeed using the Christian church as a means to cover up the misbehavior of his own troops. No matter MacArthur's motivation for inviting the Christian church to Japan, and no matter the psychological cost to many badly abused Japanese women, the establishment of the RAA was an important postwar victory for the Japanese government.

Christian missionaries very familiar with Japanese society expressed important doubt about the postwar future of the Christian church in Japan. Accordingly the vast majority of post-war missionaries were new to Japan. These two facts suggest strongly that MacArthur was poorly informed about Japanese society, was philosophically arrogant, or was indeed using the Christian church as a means to cover up the misbehavior of his own troops. No matter MacArthur's motivation for inviting the Christian church to Japan, and no matter the psychological cost to many badly abused Japanese women, the establishment of the RAA was an important postwar victory for the Japanese government.

Sources:

- Kenny Joseph. No Date. From MacArthur Missionaries to McDonald Missionaries. Parts 1 and 2. [online document | reserve] R.E.A.P. Mission Inc.宗教法人全国キリスト教伝道会. Japan Articles (downloaded on 29 October 2009).

- America Magazine, The Editors. 1942. A Look at Postwar Japan. Three editorial articles including "Japan on a New Road", "Faith in the Orient" and "Nagasaki Anniversary" [online document | reserve] (downloaded on 28 October 2009).

- Time Magazine. The Future of Jap Missions. 26 March 1945. [online document | reserve] (downloaded on 28 October 2009).

![]() The phrase "white man's burden" was coined in 1899 by Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936) in his poem of the same name. Kipling was a British subject who chronicled the British colonization of India in the 19th century. The poem is said to have appeared in response to the United States' acquisition of the Philippines.

The phrase "white man's burden" was coined in 1899 by Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936) in his poem of the same name. Kipling was a British subject who chronicled the British colonization of India in the 19th century. The poem is said to have appeared in response to the United States' acquisition of the Philippines.

The poem received praise from Teddy Roosevelt and others in search of moral justification for their exploitative expansionist policies on the North American continent, in the Western Pacific, and elsewhere. Though less poetically, George Orwell appears to have captured the spirit of the times more accurately when in 1942 he called Rudyard Kipling a "jingo imperialist" and referred to him as "the prophet of British imperialism".

Sources:

- Rudyard Kipling. 1899. "The White Man's Burden". McClure's Magazine. London: S.S. McClure's Co. (February issue). [online document | reserve]

- George Orwell. 1942. Rudyard Kipling. Horizon. London: Horizon (February issue). [online document | reserve]

![]() A common practice in many Japanese households is to celebrate the birth of a child at a Shintō shrine神社, the wedding of a son or daughter at a Christian church聖堂, and the death of a family member in a Buddhist temple寺. Many Japanese lovers celebrate the Christmas holiday shacked up at a love hotel, and I have even heard O'Tannenbaum played in the middle of summer at Tōkyō Station東京駅. Of course, there are those Japanese who take the Christian faith seriously, regularly attend church, and pray to their God.

A common practice in many Japanese households is to celebrate the birth of a child at a Shintō shrine神社, the wedding of a son or daughter at a Christian church聖堂, and the death of a family member in a Buddhist temple寺. Many Japanese lovers celebrate the Christmas holiday shacked up at a love hotel, and I have even heard O'Tannenbaum played in the middle of summer at Tōkyō Station東京駅. Of course, there are those Japanese who take the Christian faith seriously, regularly attend church, and pray to their God.

![]() Though MacArthur was generally an advocate of the free press and understood its political importance in a working democracy, he did not hesitate to avail himself to Japan's national and local media channels to spread US occupation propaganda and censor Japanese political agendas that moved contrary to his own. Chief among these latter were the cultivation of MacArthur's local public image as Japan's post-war mentor元師, the discouragement of pro-communist political activity, the dismantlement of Japan's landed aristocracy地主階級, and MacArthur's domestic political image in the US.

Though MacArthur was generally an advocate of the free press and understood its political importance in a working democracy, he did not hesitate to avail himself to Japan's national and local media channels to spread US occupation propaganda and censor Japanese political agendas that moved contrary to his own. Chief among these latter were the cultivation of MacArthur's local public image as Japan's post-war mentor元師, the discouragement of pro-communist political activity, the dismantlement of Japan's landed aristocracy地主階級, and MacArthur's domestic political image in the US.

Sources:

- David E. Kapalan. 1997. "U.S. Propaganda Efforts in Postwar Japan". JPRI Critique, Vol.4, No. 1 (February 1997) [online reserve].

- Richard Hanson. Joining the Press Club That Was Made for You. War Stories. [online document | reserve] The Foreign Correspondents Club of Japan社団法人日本外国特派員協会. (downloaded on 30 November 2009).

- Time Magazine. 1942. The Press. "Correspondents Down Under". [online document | reserve] (downloaded on 30 November 2009). Apparently MacArthur's attitude had changed during the course of the war.

![]() The term protective national agenda in this context refers to an important theme of this book -- namely, a likely concerted effort on the part of many Japanese to minimize the interference of the US military in Japanese internal affairs.

The term protective national agenda in this context refers to an important theme of this book -- namely, a likely concerted effort on the part of many Japanese to minimize the interference of the US military in Japanese internal affairs.