Passive Resistance

The United States is often given credit for Japan's miraculous postwar comeback. Important in this regard is the financial aid package that the Japanese received under the Marshall Plan and the important social, political, and economic reforms introduced under General MacArthur's GHQ command. Although such praise has likely gone a long way toward nourishing friendly ties between the peoples of the United States and Japan, there is little reason to believe that the governments of Japan and the United States were not simply protecting their nation's, respective, best interests. Obviously, General MacArthur was no Ghenghis Khan, and the world learned an important lesson about post-conflict resolution from the United States, but this is where the line should likely be drawn on exceptionally good behavior on the part of the US government.

In the end, however, one cannot understand the US role in Japan's recovery without understanding the nature and degree of cooperation that the Japanese government afforded GHQ. In this way, one can also better understand the mind-set of contemporary Japan vis-à-vis the United States, its closest Asian neighbors, and its own historical development. In brief, it appears naïve to believe that the Japanese people simply did as they were told by the United States government -- this, despite the unconditional surrender無条件降伏 to which the Japanese emperor so graciously accepted on behalf of his own people.

In order to understand the nature and degree of cooperation it is useful to compare the post-war occupation of Japan with other recent forms of occupation -- in particular, the German occupation of France leading up to World War II, the Allied occupation of Germany during the immediate post-war period, and the US occupation of Iraq after the fall of Saddam Hussein.

In addition, this section examines what would have been the expected result, if GHQ's reforms had been strictly implemented and what actually occurred as evidenced by the current state of Japanese society.

taming the defeated

Europe had barely recovered from World War I, and Germany was already pounding on its neighbors' door with an invitation to endure more of the same. Indeed, the Maginot Line would soon be crossed in a surprise attack, and the German army would pour into France largely unopposed. For the French things could have become much worse very quickly, but did they did not -- well, at least not right away.

When the Germans moved into Paris in June 1940, the French government had already fled to Bordeaux. Shortly thereafter an armistice was signed between the French and Germans at a historic location near Compiègne. This agreement resulted in the division of France into several administrative zones and the transfer of the French capital from Paris to Vichy, a central location in the north of the so-called free zone (zone libre). Although the new government already established under the French Marshall, Philippe Pétain, in Bordeaux would continue to rule over the entire French nation and its territorties, the national sovereignty of France had been severely compromised Important pockets of armed resistance developed during the German occuaption of France. There is little evidence of armed resistance in Japan under the US occupation. by the agreement, and the republican character of the French state gradually eroded as a result. As the German occupation was largely disliked, important pockets of armed resistance developed. This underground movement targeted both the German military and French officials perceived as traitors by the French resistance.

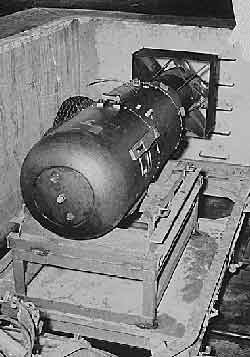

Unlike France, which had been quickly occupied by the German army and suffered little physical damage as a result, Japan would be devastated by incessant bombing raids and four long years of impoverishing war production. Two of Japan's largest cities including Nagasaki and Hiroshima would simply vanish with the explosion of two separately detonated atomic bombs, and some three-quarters of Tōkyō would be destroyed by incendiary (napalm) bombs. In the end, the Japanese would be compelled to choose between total anihilation and unconditional surrender. In this latter regard, Germany's fate was little different. The devastation was widespread, the surrender was unconditional, and the occupation was complete. Furthermore, we read little in the literature of post-war Japan and Germany about the sort of underground movements of armed resistance that were so commonplace in occupied France. Of course, this is not to say that they did not occur. Simply, the French resistance eventually overthrew their oppressor and could sing praise; the Germans and the Japanese succumbed.

Unlike Japan and Germany, France had suffered little structural damage during the German occupation.Surely there were many Japanese and Germans who saw their nation's occupation as a desirable change of guard and an important opportunity to assert themselves as a part of their nation's new national leadership. This said, occupation is rarely well-received by anyone, as few people find it easy to take orders from the military command of an alien culture with whom they share little cultural affinity. Then too, neither the Germans, nor the Japanese had little much choice in the matter. Their economies were in shambles, and they were being offered an opportunity to rebuild, if only certain conditions could be met. These circumstances must have made it easier for those eager to take the reigns of government to muster popular public support. Accordingly, it must have been difficult for those with dissenting opinion to organize openly.

Surely there must have been many other similarities, but these appear to be the most important.

very different circumstances

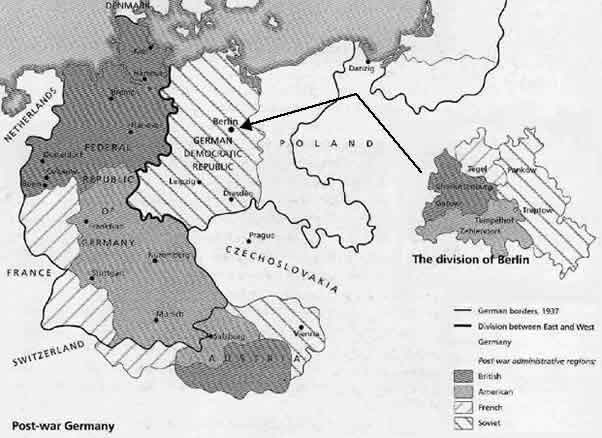

Whereas Germany was divided into four zones and occupied by four Allied Powers including the French, British, Russians, and Americans, Japan remained whole, and for all effects and purposes, only occupied by the United States.Though Japan and Germany had met a similar fate, the occupation of their lands took place under very different circumstances. Furthermore, whereas the Japanese people would continue to stand behind their fallen emperor, Hitler's response to unconditional surrender was a long awaited marriage and a romantic suicide with his beloved mistress, Eva Braun. There were other important differences.

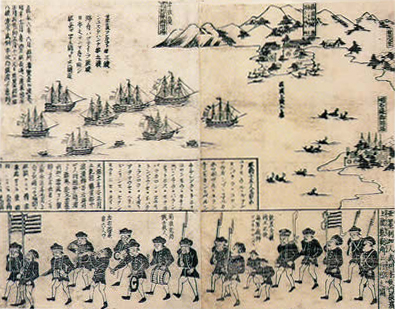

Unlike Germany whose language and culture were well known by the Allies, the Japanese language and culture was poorly understood by much of the West. In further contrast, the European continent had been at war off-and-on for many centuries; the Japanese conquest of far flung overseas territory was only recent, and Japan's experience with colonial powers on its own territory was, comparatively speaking, limited. France had occupied large swaths of the west German border on not a few occasions, and Napolean's conquest of Europe will likely never be forgotten. In juxtaposition, Japan lived for many centuries with a closed door policy. Even after its doors were finally forced open in the mid-19th century, the Japanese remained in charge of their own fate. The Japanese understood colonial accommodation. In contrast, what they new of colonial exploitation and oppression was largely what they had learned from their European and North American mentors and inflicted on their closest neighbors. Japan had never in recent history been completely occupied by anyone.

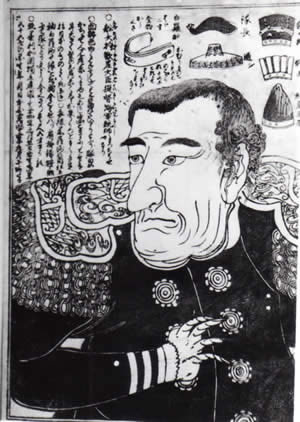

america's second coming

After Admiral Perry arrived in Uraga in 1853 the Japanese government began a long period of bitter internal political struggle to decide an appropriate strategy to ward off the threat of further colonization. During this period political assassination and social unrest were commonplace, and Japan passed through one of the most important and difficult philosophical and strategic debates of its historical development. An important outcome of this struggle was the decision to modernize, for only in this way could Japan avert being exploited on behalf of someone else's modernization. So effective was the implementation of this new policy that within only decades Japan would be doing to its closest neighbors what it had once feared distant colonial powers would be doing to it.

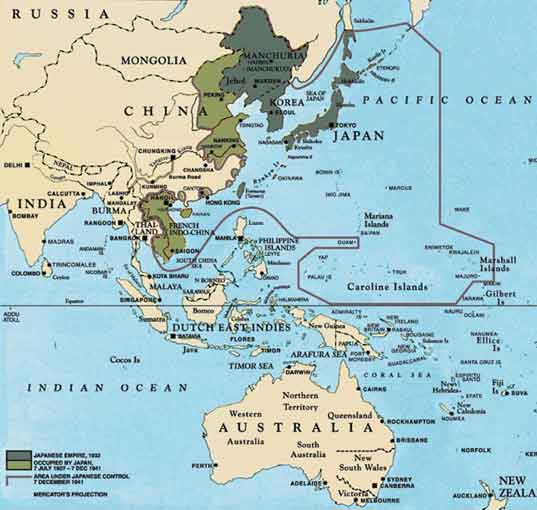

By creating its own empire in East Asia Japan would be able to stand firm against US and Russian expansionism in Northeast Asia.The building of a colonial empire was a relatively new phenomenon for Japan -- an activity for which it was not entirely ready. Strategically speaking, Japan was on the right track; Russia and the United States were standing on Japan's threshhold, and colonial empire building was the unfortunate state of current world affairs. Japan's problem lay, however, in its relative newness to overseas empire building -- an activity for which it was only partially ready.

The period between the first appearance of Admiral Perry and the arrival of General MacArthur was hardly one of steady engagement with the United States, however. During this relatively short interval Japan's importation of knowledge and technology from the European continent and Great Britain was substantial. It was only after Europe became embroiled in World War I, and trade with Europe became difficult, that Japan's commercial ties with the United States assumed noticeable importance. Indeed, Japan's long standing relationship with Great Britain made the transition from trade with Europe to trade with the United States a relatively easy task. By the time the war was over, Japan and the United States probably knew each other better as vicious enemies than former trading partners.Unfortunately, even this relationship was destined to fail, as Japan's imperial design soon began to threaten US interests in the Far East. Thus, by the time World War II was over, Japan and the United States probably knew each other better as vicious enemies than former trading partners.

Culturally speaking, Japan and the United States share little in common, for in the end social change always lags behind technological innovation. Moreover, separated geographically by the world's largest ocean, Japan and the United States have followed very different historical and philosophical paths. When US troops landed in France, they were greeted as liberators; when they landed in Japan, they were received as conquerors.

Certainly Japanese-Americans living in the United States received very poor treatment during the war and were often rejected after its conclusion.

mixed feelings

There must be many Japanese brought up during the reconstruction era who have good memories of the US occupation. During the war the United States was portrayed as a brutal, rapacious enemy. Upon their arrival, however, rather than pillaging the Japanese countryside the relatively well-disciplined US troops engaged in Japan's lucrative postwar black market and provided badly needed foodstuffs and other scarce supplies in exchange for cultural souvenirs and local entertainment. There were also important infusions of food and medical supplies that brought important relief to a nations ravaged by war. In addition, many Japanese entrepreneurs were eventually able to take advantage of the modest benefits offered by the Marshall Plan including grants-in-aid, low-interest loans, and easily accessible foreign markets.

In contrast, there must have been many other Japanese who found the participation of US soldiers in Japan's postwar black market distasteful, damned the US for frustrating Japan's attempt to build an empire in East Asia, and viewed the US as an alien presence whose early departure they would do their utmost to encourage.

Unlike in Germany, where well over a third of war-time government officials were purged from office, some 90 percent of Japan's wartime bureaucracy retained their desks.It is estimated that some 90 percent of Japan's national bureaucracy remained in place after the war. This is in stark contrast to what happened in Germany. Many of these bureaucrats had just spent anywhere from four to forty years thinking of ways to enhance Japan's imperial preeminence in East Asia. Thus, it is likely that a significant amount of the cooperation demonstrated by the Japanese government vis-à-vis the United States was opportunistic in nature and hardly motivated by a very strong desire for friendship.

The number of Japanese who had lost their homes, families, friends, and places of work must have been large, and their suffering very real. Even more, the estimated 350,000 US troops scattered across Japan during the post-war occupation must have been salt in the wounds of this unfortunate many -- a daily living reminder of their nation's humilating and brutal defeat.

By the time the children of these unsung heroes joined the ranks of Japan's government and industrial work force, their parents were sitting on the boards of Japan's large corporate enterprises (kaisha会社), industrial groups, and national financial and industrial associations. To no less extent many of those who rebuilt Japan's factories, warehouses, and offices and who manned the machines and desks of Japan's newly formed companies were the same who had fought in China and Southeast Asia in defense of their beloved emperor. The number of war stories told by these parents as they worked their way up their respective bureaucratic, corporate, and factory ladders is surely too many to count. More importantly, nearly all of these stories were likely told under the radar of government public censorship.

Many of these parents became the teachers and mentors of these same children who would later read in history textbooks about Admiral Perry's Black Ships (kurofune黒船), the Tōkyō firebomb raids, and Hiroshima広島 and Nagasaki長崎.

Nor can one assume that serious bitterness towards the United States did not remain. History textbooks which appeared just after the war portrayed Japan's wartime leadership as a group of fascist elite, who had led their country down an improper path. Nevertheless, there are few, if any monuments to remind Japanese children of their forefathers' war crimes. Places such as Sugamo Prison巣鴨藍獄, which could have served well in this capacity were demolished in the name of economic progress. What one finds instead is a condemnation of the United States for its indiscriminate destruction of human life at Hiroshima's Peace Memorial広島平和記念公園 and a celebration of Japan's wartime leaders at the controversial Yasukuni Jinja靖国神社 in Tōkyō東京. Comparing the messages of these historical artifacts with those of Berlin's reconstructed Reichstag and Nürnberg's renovated courthouse leaves one to wonder whether Germany and Japan were not on different sides of the same war. Was the Japanese nation any less guilty of international aggression and war crimes than their German counterpart? Are German ancestors less worthy of praise than those of the Japanese? How one remembers the past determines, in part, one's ability to cope with the future.Is the United States somehow more guilty than the Japanese of crimes against humanity? Surely, putting an ugly past aside so that one can move forward into the future is an important matter. Failing to remind our children of the dangers of irresponsible government in the name of national unity and industrial progress is quite another. Perhaps the Japanese believe that their peace constitution日本国憲法 is reminder enough of their nation's tragic past. Certainly, it remains as the symbol of a wishful future.

historical obfuscation

For better or for worse, what Japanese parents and grandparents have obscured from their own children and grandchildren, they have been unable to conceal from the children and grandchildren of their closest neighbors and others deeply affected by Japan's ignomious past. In the end, this obfuscation has served to isolate Japan from the rest of the world and sours an otherwise healthy relationship between Japan and its closest military ally the United States.

If you are from the West, historical discussions between the Japanese general public and Japan's foreign residents generally center around Japan's Edo period江戸時代 and the current economy. Although the focus of attention shifts, if you are from East or Southeast Asia, the ability of many Japanese to engage in meaningful historical discussion focused on the period between the landing of Admiral Perry and the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki is generally handicapped by a lack of desire or poor command of the facts. This reluctance and/or inability to discuss in a meaningful way the annexation of Korea, the invasion of Manchuria, and the military expansion of Japan across the Western Pacific distorts the Japanese perception of contemporary historical process and social evolution and cripples its ability to participate openly on the world stage.Although Japan remains in control of its own short-term destiny, its understanding of long term historical process appears to suffer from a distorted perception of its own recent past.

Rather than viewing its 20th century aggression and defeat as an important episode in the closing chapter of a global era of overseas colonial expansion begun in Europe as early as the 15th century, the Japanese prefer to view themselves as victims of this era and sing praise to a period of their own history whose probable utility as an explanation of Japanese society is being rapidly eroded by current events.

When I see the blue tarps on which Japanese families sit in cemeteries and parks across the country on bright sunny days during Japan's hanami花見 season, I cannot help but sense a sardonic expression of Japan's unsought friendship with the United States.

On the one hand, these tarps are a terrestrial mirror of the blue sky they reflect; on the other hand, they are the protective ground cover on which everyone sits -- the artificial low-point of a fabricated red, white, and blue backdrop to a truly seasonal, pink, Japanese ritual. Of course, in Tōkyō's Ueno Park上野公園, where thousands of lanterns cast their magical iridescence against an overhead canvas of sheer darkness at the close of a long spring day, the only blue to be found is that upon which everyone is sitting.

Then too, all that is in the sky during the day is not blue. On the weekend large, black crows fly from one lofty perch to the next in relentless dialogue among the red and white blossoms that populate the cherry trees of Somei Reien, a Japanese cemetery located close to Sugamo Station巣鴨駅. On Monday morning it is politics as usual as the crows return to pillage the plastic garbage sacks, dutifully wrapped and stacked by the prior weekend's party-goers. One cannot help but think that Japan's oldest early risers are not reminded of the rubble that they once collected and stacked as children at the close of World War II. Certainly the crows are a symbolic reminder to everyone of Japan's ongoing political corruption.

Many foreigners are astounded by the admiration that Japanese typically express toward the United States, but do they understand the underlying political and economic dynamic that motivates these sometimes deeply held pleasantries?

During the early post-war period General MacArthur issued what are entered into Japanese history books as the godaikaikakushime五大改革指命 -- a brief, but detailed list of five major reforms that the Japanese government was instructed to undertake before the United States would return control of the Japanese nation to the Japanese government. This list included the liberation of the Japanese woman, the reformation of Japan's educational system, the liberalization of Japan's means to production, the organization of trade unions, and the end of the use of arbitrary force. The purpose of these demands was to insure the democratization of the Japanese state.After some 60 years of internal political struggle MacArthur's reforms have still not been fully realized. This said, Japan's "OL"s (office ladies) continue to serve tea in government and business offices throughout the country; the Japanese public school system is still nationally controlled and tightly regulated; Japan's renown keiretsu系列 remain a strong, behind-the-scenes, political force; Japanese organized labor persists as a loosely knit confederation of company-bound unions; and the legally unsanctioned right of Japanese police to enter the houses of Japanese residents without a search warrant is all too apparent. All of this suggests strongly that the significant changes that Japan has witnessed since the close of the war are still far removed from those once envisioned by the United States government.

putting faith in one's enemy

Though it is true that Japanese have been studying English since the Meiji Restoration明治維新, this study has not been without its ups and downs. When the language was first introduced into the Japanese educational system, it was but one of several languages employed by invited European and North American scholars to teach Western technology, science, and culture to a handful of Japan's very best students. In time these instructors were replaced by Japanese who taught the same subjects in Japanese or the language of their previous foreign mentors. Few Japanese could speak any European language, let alone read or write one. In time English was introduced into Japan's grade school classrooms, where it was likely taught using many of the same teaching methods used to teach Japanese children in public schools today -- namely, as a passive reading tool mastered for the purpose of passing advanced level entrance examinations, acquiring Western technology, and understanding overseas business contracts. During World War II English was banned from the public school system altogether, and the English language print disappeared from public view.

When US American troops landed in Japan, it is likely that one could have counted the number of Japanese-speaking US military personnel with the number of fingers and toes on the male-side of a popular Tōkyō sentō洗湯.One could probably have counted the number of bilingual US citizens among the occupation forces with the toes and fingers on the male side of a popular Tōkyō sentō According to a French historian important language differences posed a major problem at the trials of Japanese war criminals. Indeed, if a sufficient number of qualified bilingual experts were not available to conduct properly what was probably one of the most important trials in Japanese history, then one can easily imagine how difficult it must have been to understand and execute the socio-economic reforms dictated by GHQ. In short, the US government must have depended significantly on the good-will of its defeated enemy to implement these reforms -- the same enemy who just a few months before was ready to go to its grave in defense of its emperor.

That those Japanese who could speak English well enough to perform the necessary liaison between US troops and their Japanese hosts were very much different from those who sit today across the negotiation table during trade talks between the US and Japanese governments is difficult to imagine. Contemporary Japan-US trade agreements typically fail because US negotiators have such a poor understanding of how Japanese society functions. Thus, even if GHQ orders had been properly translated and interpreted, one cannot help but wonder how successfully they were carried out by those Japanese appointed to do so. The rapid dissolution of the GHQ was surely less an indication of its success than a matter of historical expediency and the Japanese art of deceptive compliance. Successful comprehension of reports submitted by Japanese officials to their US superiors detailing the extent to which reforms had or had not been implemented must have been even more baffling. The rapid dissolution of the GHQ was surely less an indication of its success than a matter of historical expediency and the Japanese art of deception.

appearances

Japan is an ancient culture that has had much time to develop nuances of language and custom that younger cultures do not share. As such, even those among the occupation forces who could speak Japanese well enough to hold a conversation would not have been able to penetrate the many subtle and hidden interpretations of meaning contained in words and symbols that easily touch the hearts and minds of local inhabitants, but escape the foreigner's attention.

The artists and entertainers in whom we delight most are those who interpret single words and phrases, customs, manners, and events from a variety of perspectives with which we are all well-acquainted because of our long association with a particular society, language, and culture. In the end, how many foreigners visiting Japan then, and even many of those who live and work there today, can even tell the difference between in入 or out出, up上 or down下, push押 or pull引, and male男 or female女, when the Japanese symbols for these opposites appear directly before their eyes? Indeed, just how does one successfully monitor a host nation's thought and behavior when one knows neither the language, nor the culture of one's hosts? Truly, one cannot.In the absence of good knowledge of Japanese language and culture it must have been very difficult to monitor the implementation of postwar reforms.

the evidence

Had there been little resistance, as many Japanese and Americans would have us believe, the aforementioned reforms would likely have been lost in translation.

So just how much was MacArthur's GHQ able to accomplish? Although some would argue quite a bit, others would argue not very much. This is not to criticize the US government for not doing the best with what it had; simply it did not have very much. If the US government's uderstanding of what to expect after the invasion of Saddam's Iraq is any indication of the US government's knowledge of Japanese society when it entered Tōkyō Bay東京湾, uninvited for the second time, some 60 years ago, then one can easily imagine that the liberalization of Japanese society and the democratization of Japan's political system were little more than well-stated public goals that took a back-seat to securing bases for US overseas operations against the Soviet Union and Communist China.

The Japanese state today, though quite small according to the number of people who appear on the national government's payroll, is enormously powerful and remains highly centralized. Japanese ex-bureaucrats fill the ranks天下り of Japanese corporate and bank executive boards, preside over countless semi-private business and civic associations社団法人, and research institutions, and dictate the affairs of Japan's major universities. Moreover, Japan's public school system is administered by the national government and carefully monitored by Japan's Ministry of Education文部科学省. Though each prefecture県庁 has control over its own budget targets, Japan's Ministry of Finance (MOF財務省) has considerable say in how these budgets are financed.

When Japan's Big Bubble burst in the early 90's and the full extent of the debt was finally understood, many local governments that had run healthy financial ships before the crisis were called on to bail out the national government. Though a major overall of Japan's private sector financial system ensued, the economic integrity and political clout of Japan's tightly integrated industrial groups were retained. The dozen or so main banks主要銀行 on which these groups once depended were dismantled, but re-emerged as a small number of megabanks with ever greater financial and political clout. The industrial power of these groups is converted into political power via exclusive presidential clubs such as the keidanren経団連 and closely knit distribution keiretsu流通系列 that cross local community boundaries. Although the stock of the companies that constitute these groups are publicly traded, the companies themselves remain closely bound through intragroup cross-share holdings and lending practices. Separately and together, these groups behave in a manner very similar to Japan's prewar, privately owned and managed zaibatsu財閥. After some 60 years of major social, economic, and political transformation one could argue that very little has changed in Japan.They control prices, restrict competition, dissuade both domestic and foreign entrants, and wield enormous political clout at all levels of government. For more than 60 years the jimintō自民党 (Liberal Democratic Party) greased the wheels of corruption between these powerful industrial groups and Japan's national bureaucracy -- a bureaucratic machine that has ruled Japan, except for minor pause under the GHQ, since the late Meiji明治 era. Japanese politics is often compared with kabuki歌舞伎, a Japanese theatrical tradition that flowered in Japan during the height of the Edo江戸 period. Indeed, some maintain that Japan's political parties serve as little more than an entertaining media diversion that buffers Japan's national bureaucracy -- the true holders of power in Japanese government -- from a largely apolitical, but highly critical general public.

Though individual citizens have the right to go to court in Japan, with the exception of large corporations few Japanese make use of their judicial system to resolve disputes. This is because the cost and time it takes to render verdicts is usually prohibitive. The result is obvious, everyone tries to get along with everyone else, and good relations with the holders of power are carefully cultivated. Perceived personal injustices can be settled in any number of ways including alcoholic indulgence, special favors from those in power, endless discussion with one's colleagues, friends, or neighbors, petty acts of vengeance, suicide, and more.

Only now that large Japanese firms have found it difficult to compete in certain world markets, because the cost of domestic productive inputs are prohibitively high or simply scarce, has a secondary labor market begun to reappear. Until recently Japanese workers wanting to leave their companies in mid-career could not, because of a tacit agreement among Japanese employers not to hire workers from other companies.

In Japan there are few scholarly journals with stiff review committees whose members span a broad spectrum of academic institutions. With friends in the right place one can publish just about anything, and the more that one publishes the greater hearing one receives, whether what is said has any scientific value or not. What is true and not true in Japan is more determined by whom you know and your ability to persuade, rather than by what you know. The Japanese press, although free to publish what it wants, is often at the mercy of those who provide the information that it wants to publish. Those who publish what the government wants to have read receive information, and those who publish information to the contrary receive none.

The Japanese consumer is free to buy what and where he wants, but that which is available for purchase is carefully filtered by numerous distributive and productive chains, which are difficult to break into. Retail merchants are tightly controlled by wholesale suppliers, who threaten to cut their supply of goods and credit, if disloyalty on the part of the retailer is detected. As a result, not only are consumers unable to obtain everything they would like, but they are often ignorant about what is truly available.

Although Japanese medical care is quite good, the treatment that one receives is limited by the knowledge of one's physician. Like the wholesaler to his retailer, Japanese physicians demand patient loyalty and generally do not advise their patients to obtain second and third opinions. As a result patients are sometimes mishandled and diagnoses are improper. This is not to say, however, that Japan does not have one of the best public health care systems in the world.

closing remarks

It would be difficult to attribute Japan's success to its political democracy and understanding of recent historical events.Ironically, when all is said and done, Japanese society often functions better than other societies of the modern world. This is not because it is particularly liberal or even democratic, however. Nor, is it because the Japanese people have a very good understanding of historical process.

![]() The Maginot Line (ligne Maginot) was a defensive line of military fortification constructed by the French along the French-German border during the 1930's. It was opposed by Charles de Gaulle and others who favored mechanized warfare over the static entrenchment proposed by Marshall Joseph Joffre. Project construction began under the leadership of André Maginot, the French Minister of War, after whom the line was named. The Maginot Line failed to prevent Germany's invasion of France in May 1940 and its eventual occupation of the French nation until June 1944.

The Maginot Line (ligne Maginot) was a defensive line of military fortification constructed by the French along the French-German border during the 1930's. It was opposed by Charles de Gaulle and others who favored mechanized warfare over the static entrenchment proposed by Marshall Joseph Joffre. Project construction began under the leadership of André Maginot, the French Minister of War, after whom the line was named. The Maginot Line failed to prevent Germany's invasion of France in May 1940 and its eventual occupation of the French nation until June 1944.

![]() Statement from a copy of the Cairo Communiqué -- a summary of key statements agreed upon by President Roosevelt, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, and Prime Minister Mr. Churchill in Cairo and scheduled for release on December 1, 1943. National Diet Library. Repository: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration (RG59)

Statement from a copy of the Cairo Communiqué -- a summary of key statements agreed upon by President Roosevelt, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, and Prime Minister Mr. Churchill in Cairo and scheduled for release on December 1, 1943. National Diet Library. Repository: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration (RG59)

- The Three Great Allies are fighting this war to restrain and punish the aggression of Japan. They covet no gain for themselves and have no thought of territorial expansion. It is their purpose that Japan shall be stripped of all the islands in the Pacific which she has seized or occupied since the beginning of the first World War in 1914, and that all the territories Japan has stolen from the Chinese, such as Manchuria, Formosa, and The Pescadores, shall be restored to the Republic of China. Japan will also be expelled from all other territories which she has taken by violence and greed. The aforesaid three great powers, mindful of the enslavement of the people of Korea, are determined that in due course Korea shall become free and independent.

With these objects in view the three Allies, in harmony with those of the United Nations at war with Japan, will continue to persevere in the serious and prolonged operations necessary to procure the unconditional surrender of Japan.

![]() Articles 7 and 12 of the Potsdam Declaration defining the terms for surrender issued in Potsdam in 1945. National Diet Library. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Nihon Gaikō Nenpyō Narabini Shuyō Bunsho日本外交年表並びに主要文書: 1840-1945, vol.2, 1966.

Articles 7 and 12 of the Potsdam Declaration defining the terms for surrender issued in Potsdam in 1945. National Diet Library. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Nihon Gaikō Nenpyō Narabini Shuyō Bunsho日本外交年表並びに主要文書: 1840-1945, vol.2, 1966.

- 3. The result of the futile and senseless German resistance to the might of the aroused free peoples of the world stands forth in awful clarity as an example to the people of Japan. The might that now converges on Japan is immeasurably greater than that which, when applied to the resisting Nazis, necessarily laid waste to the lands, the industry and the method of life of the whole German people. The full application of our military power, backed by our resolve, will mean the inevitable and complete destruction of the Japanese armed forces and just as inevitably the utter devastation of the Japanese homeland.

- 7. Until such a new order is established and until there is convincing proof that Japan's war-making power is destroyed, points in Japanese territory to be designated by the Allies shall be occupied to secure the achievement of the basic objectives we are here setting forth.

- 12. The occupying forces of the Allies shall be withdrawn from Japan as soon as these objectives have been accomplished and there has been established in accordance with the freely expressed will of the Japanese people a peacefully inclined and responsible government.

![]() Between the beginning of the Meiji Restoration and the beginning of World War II less than a century had passed. In effect, those in charge of Japan's imperial collapse were the grandchildren of those who had given rise to its creation.

Between the beginning of the Meiji Restoration and the beginning of World War II less than a century had passed. In effect, those in charge of Japan's imperial collapse were the grandchildren of those who had given rise to its creation.

![]() Already before the attack on Pearl Harbor, US Congressman John D. Dingell, Sr. of Michigan recommended in a letter to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt that the movement of Japanese-Americans living in Hawaii be restricted. By the time the war ended several years later over 120,000 Japanese-American mainlanders had been forcefully relocated to internment camps across the continental United States. When these internees were finally released, they were rejected by the very communities they had once called home.

Already before the attack on Pearl Harbor, US Congressman John D. Dingell, Sr. of Michigan recommended in a letter to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt that the movement of Japanese-Americans living in Hawaii be restricted. By the time the war ended several years later over 120,000 Japanese-American mainlanders had been forcefully relocated to internment camps across the continental United States. When these internees were finally released, they were rejected by the very communities they had once called home.

- Public Broadcasting Service. Children of the Camps. Internment History. Historical Timeline. Unfortunately a copy of the aforementioned letter was not available. (downloaded on 7 September 2009)

- US Department of the Interior. National Park Service. National Historical Site. Manzanar, California. (downloaded on 7 September 2009)

- Denshō. Sites of Shame. (downloaded on 7 September 2009)

- Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library. National Archives and Records Administration. Official File: 197, Japan 1941-1942 (Box 1). Letter from US Representative John Dingell, Sr. to the President including a memorandum written by the President and a reply to Congressman Dingell from Secretary of State Cordell Hull. Hyde Park, New York. Contact roosevelt.library@nara.gov.

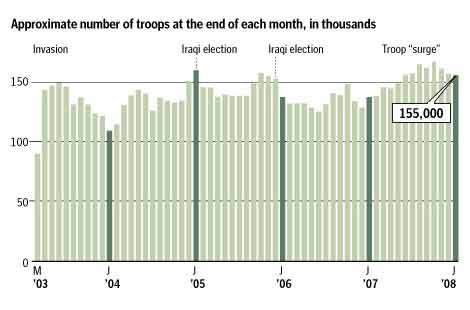

![]() In 1948 the population of Japan was about 2.8 times larger than the population of Iraq in 2007. In the fall of 2007 the number of US troops in Iraq peaked at 168,000 -- fewer than half the number of US troops in Japan in 1948. This means that for every one US soldier in Japan there were some 239 Japanese. In Iraq the ratio was about one US soldier to every 173 Iraqis.

In 1948 the population of Japan was about 2.8 times larger than the population of Iraq in 2007. In the fall of 2007 the number of US troops in Iraq peaked at 168,000 -- fewer than half the number of US troops in Japan in 1948. This means that for every one US soldier in Japan there were some 239 Japanese. In Iraq the ratio was about one US soldier to every 173 Iraqis.

Although geograpically very different places, Iraq and Japan are similar in one important way: their respective populations are concentrated over only a small fraction of their respective land areas. Whereas much of Iraq is desert and most of the population lives in close proximity to two major river basins, most of Japan is mountainous, and Japanese tend to live near the sea. Today, some 85% of all Japanese occupy only 14% of Japan's total land surface and the majority of these live in a narrow corridor between Ōsaka and Tōkyō. If we compare the surface area of these two countries, there was one US soldier for every 1.1 sq.km. of Japanese soil, but only one for every 2.6 sq.km. of Iraqi soil.

In which country were US troops more visible at the peak of their respective operations; it is difficult to say. That communication was difficult in both countries is most certainly the case. Weapons of mass destruction aside, however, is it not obvious that the United States had far better information of Iraqi culture and language when it invaded Iraq, than it did of Japanese language and culture when it entered Japan?

Sources:

- United Nations Data Query.

- The Washington Post. US Troop Strength in Iraq. Monthly data from 2003 to 2008. [online document]. (downloaded 25 September 2009).

![]() For a brief discussion of the arrangement of burial plots at Somei Reien染井霊園 and a more thorough examination of the derivation of the first registered Japanese name by a foreign resident in Naka-ku, Yokahama-shi横浜市中区 see Hashimori Iwato橋守岩人 - The Derivation of My Name.

For a brief discussion of the arrangement of burial plots at Somei Reien染井霊園 and a more thorough examination of the derivation of the first registered Japanese name by a foreign resident in Naka-ku, Yokahama-shi横浜市中区 see Hashimori Iwato橋守岩人 - The Derivation of My Name.

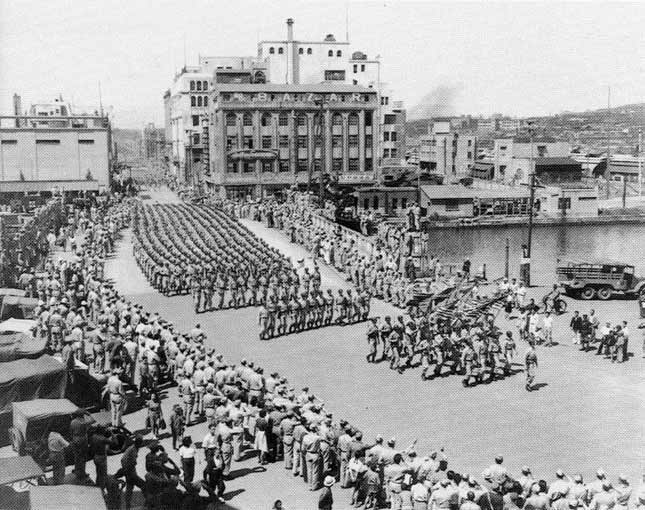

![]() The 1945 (Shōwa 20昭和20年) Potsdam Declaration placed Japan under control of the Allied Powers. Apparently there had been a plan to divide and occupy Japan just as Germany had been divided and occupied in Europe. Fortunately, for Japan this plan was never implemented, and the United States military assumed effective control of the occupation under the command of General Douglas MacArthur, who directed the occupation from his General Headquarters (GHQ) as the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP).

The 1945 (Shōwa 20昭和20年) Potsdam Declaration placed Japan under control of the Allied Powers. Apparently there had been a plan to divide and occupy Japan just as Germany had been divided and occupied in Europe. Fortunately, for Japan this plan was never implemented, and the United States military assumed effective control of the occupation under the command of General Douglas MacArthur, who directed the occupation from his General Headquarters (GHQ) as the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP).

Unlike many wartime artifacts in Japan that were destroyed as a means to erase an unpleasant memory, the old GHQ building was preserved and today forms a part of the newer Daiichi-Seimei building located just opposite the Emperor's Palace in downtown Tōkyō.

![]() By December 2003 five new megabanks had been created and further subsequent consolidation appears to have reduced this number to four including: Mizuho Financial Groupみずほフィナンシャルグループ, the Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group三井住友銀行, the Mitsubishi Tokyo UFJ Financial Group三菱東京UFJ銀行, and Resona Holdingsりそなホールディングす.

By December 2003 five new megabanks had been created and further subsequent consolidation appears to have reduced this number to four including: Mizuho Financial Groupみずほフィナンシャルグループ, the Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group三井住友銀行, the Mitsubishi Tokyo UFJ Financial Group三菱東京UFJ銀行, and Resona Holdingsりそなホールディングす.

Although the Kawai Masahiro河合正弘 article (see below) indicates that five new megabanks were formed, evidence found on the internet shows that the Mitsubishi-Tokyo Financial Group and UFJ Holdings have since merged into the Mitsubishi Tokyo UFJ Financial Group.

Source: Kawai Masahiro河合正弘. 2003. Tōkyō University, Institute of Social Sciences東京大学社会科学研究所. Japan's Banking System: From the Bubble and Crisis to Reconstruction. Ministry of Finance, Policy Research Institute財務省財務総合政策研究所研究部. PRI Discussion Paper Series. No. 03A-28. p. 16. [reserve].